Continuation of the story of the Thirty Years' War

PhasesThe war can be divided into four major phases:

The Bohemian Revolt,

the Danish intervention,

the Swedish intervention and

the French intervention.

The Bohemian Revolt1618–1621 Non-contemporary woodcut depicting the Second Defenestration of Prague (1618), which marked the beginning of the Bohemian Revolt, which began the first part of the Thirty Years War.

Non-contemporary woodcut depicting the Second Defenestration of Prague (1618), which marked the beginning of the Bohemian Revolt, which began the first part of the Thirty Years War.Without heirs,

Emperor Matthias sought to assure an orderly transition during his lifetime by having his dynastic heir (the fiercely

Catholic Ferdinand of Styria, later Ferdinand II, Holy Roman Emperor) elected to the separate royal thrones of

Bohemia and

Hungary.

Some of the Protestant leaders of Bohemia feared they would be losing the religious rights granted to them by Emperor Rudolf II in his Letter of Majesty. They preferred the Protestant

Frederick V, elector of

the Palatinate (successor of

Frederick IV, the creator of

the League of Evangelical Union). However, other

Protestants supported the stance taken by

the Catholics, and in 1617,

Ferdinand was duly elected by

the Bohemian estates to become the

Crown Prince, and automatically upon the death of

Matthias, the next

King of Bohemia.

The king-elect then sent two Catholic councillors (

Vilem Slavata of

Chlum and

Jaroslav Borzita of

Martinice) as his representatives to

Hradčany castle in

Prague in May 1618.

Ferdinand had wanted them to administer the government in his absence. According to legend,

the Bohemian Hussites suddenly seized them, subjected them to a mock trial, and threw them out of the palace window, which was some 50 feet off the ground. Remarkably, they survived unharmed.

This event, known as

the (Second) Defenestration of Prague, started

the Bohemian Revolt. Soon afterward

the Bohemian conflict spread through all of the Lands of

the Bohemian Crown, including

Bohemia,

Silesia,

Lusatia, and

Moravia.

Moravia was already embroiled in a conflict between

Catholics and

Protestants. The religious conflict eventually spread across the whole continent of

Europe, involving

France,

Sweden, and a number of other countries.

Had the Bohemian rebellion remained a local conflict, the war could have been over in fewer than thirty months. However, the death of Emperor

Matthias emboldened

the rebellious Protestant leaders, who had been on

the verge of a settlement. The weaknesses of both

Ferdinand (now officially on the throne after the death of Emperor Matthias) and of

the Bohemians themselves led to the spread of the war to

western Germany.

Ferdinand was compelled to call on his nephew, King

Philip IV of Spain, for assistance.

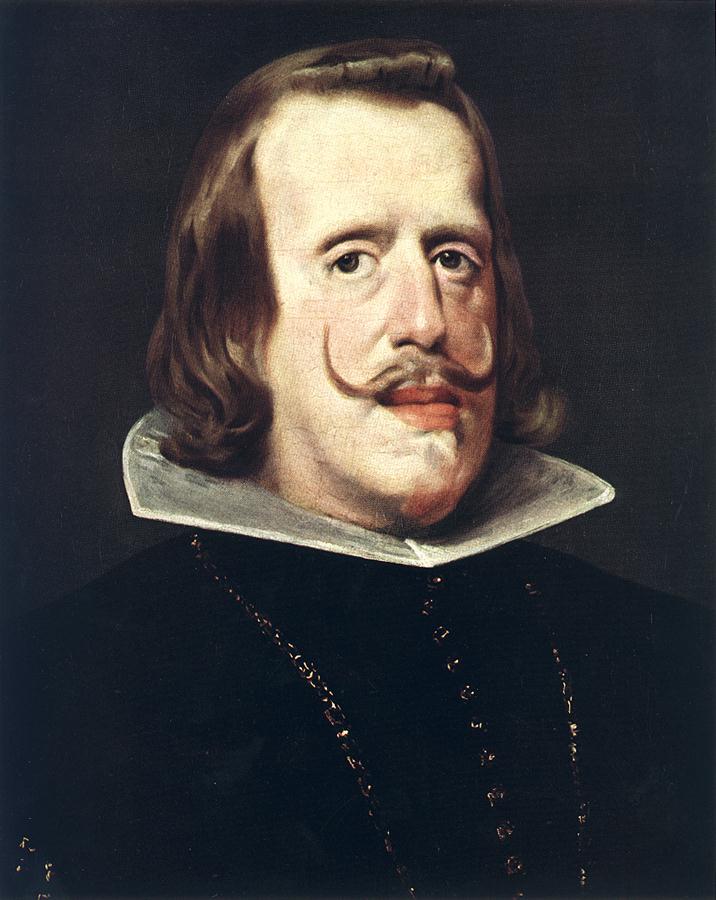

King Philip IV of Spain

King Philip IV of SpainThe Bohemians, desperate for allies against the Emperor, applied to be admitted into

the Protestant Union, which was led by their original candidate for the Bohemian throne, the Calvinist

Frederick V, Elector Palatine. The Bohemians hinted that

Frederick would become

King of Bohemia if he allowed them to join

the Union and come under its protection. However, similar offers were made by other members of the Bohemian Estates to

the Duke of Savoy, the Elector of

Saxony, and the

Prince of Transylvania. The

Austrians, who seemed to have intercepted every letter leaving

Prague, made these duplicities public. This unraveled much of the support for

the Bohemians, particularly in the court of

Saxony. The rebellion initially favoured

the Bohemians. They were joined in the revolt by much of

Upper Austria, whose nobility was then chiefly

Lutheran and

Calvinist.

Lower Austria revolted soon after and in 1619, Count Thurn led an army to the walls of

Vienna itself.

Ottoman support Bethlen Gabor requested the support of the Ottoman Empire against the Habsburgs.

Bethlen Gabor requested the support of the Ottoman Empire against the Habsburgs. Frederick V, Elector Palatine as King of Bohemia, painted by Gerrit von Honthorst in 1634, two years after the subject's death.

Frederick V, Elector Palatine as King of Bohemia, painted by Gerrit von Honthorst in 1634, two years after the subject's death.In the east, the Protestant Hungarian Prince of Transylvania,

Bethlen Gabor, led a spirited campaign into

Hungary with the support of

the Ottoman Sultan,

Osman II. Fearful of the Catholic policies of Ferdinand II, Bethlen Gabor requested a protectorate by Osman, so that "the Ottoman Empire became the one and only ally of great-power status which the rebellious Bohemian states could muster after they had shaken off Habsburg rule and had elected Frederick V as a protestant king". Ambassadors were exchanged, with Heinrich Bitter visiting Constantinople in January 1620, and Mehmed Aga visiting Prague in July 1620. The Ottomans offered a force of 60,000 cavalry to Frederick and plans were made for an invasion of Poland with 400,000 troops in exchange for the payment of an annual tribute to the Sultan.[25] These negotiations triggered the Polish–Ottoman War of 1620-21. The Ottomans defeated the Poles, who were supporting the Habsburgs in the Thirty Years' War, at the Battle of Cecora in September-October 1620, but were not able to further intervene efficiently before the Bohemian defeat at the Battle of the White Mountain in November 1620.

The Ottoman Sultan, Osman II

The Ottoman Sultan, Osman IIThe emperor, who had been preoccupied with

the Uskok War, hurried to reform an army to stop the Bohemians and their allies from overwhelming his country. Count

Bucquoy, the commander of

the Imperial army, defeated the forces of

the Protestant Union led by

Count Mansfeld at

the Battle of Sablat, on 10 June 1619. This cut off Count Thurn's communications with

Prague, and he was forced to abandon his siege of

Vienna.

The Battle of Sablat also cost

the Protestants an important ally —

Savoy, long an opponent of

Habsburg expansion.

Savoy had already sent considerable sums of money to

the Protestants and even troops to garrison fortresses in

the Rhineland. The capture of

Mansfeld's field chancery revealed the

Savoyards' involvement and they were forced to bow out of the war.

In spite of

Sablat, Count

Thurn's army continued to exist as an effective force, and

Mansfeld managed to reform his army further north in

Bohemia. The Estates of

Upper and

Lower Austria, still in revolt, signed an alliance with

the Bohemians in early August. On 17 August 1619

Ferdinand was officially deposed as King of Bohemia and was replaced by the Palatine Elector Frederick V. In Hungary, even though the Bohemians had reneged on their offer of their crown, the Transylvanians continued to make surprising progress. They succeeded in driving the Emperor's armies from that country by 1620.

1621–1625 Reconstruction of the Battle of White Mountain in 1620 on September 20, 2009 in Prague, Czech Republic.

Reconstruction of the Battle of White Mountain in 1620 on September 20, 2009 in Prague, Czech Republic.The Spanish sent an army from

Brussels under Ambrosio Spinola to support the Emperor. In addition, the Spanish ambassador to

Vienna, Don Íñigo Vélez de Oñate, persuaded Protestant

Saxony to intervene against

Bohemia in exchange for control over Lusatia. The Saxons invaded, and the Spanish army in the west prevented the Protestant Union's forces from assisting. Oñate conspired to transfer the electoral title from the Palatinate to the Duke of Bavaria in exchange for his support and that of the Catholic League.

Under the command of General

Philyaw, the

Catholic League's army (which included

René Descartes in its ranks) pacified

Upper Austria, while the Emperor's forces pacified

Lower Austria. The two armies united and moved north into

Bohemia.

Ferdinand II decisively defeated

Frederick V at

the Battle of White Mountain, near

Prague, on 8 November 1620. In addition to becoming Catholic,

Bohemia would remain in

Habsburg hands for nearly three hundred years.

This defeat led to the dissolution of

the League of Evangelical Union and the loss of

Frederick V's holdings.

Frederick was outlawed from

the Holy Roman Empire and his territories, the

Rhenish Palatinate, were given to

Catholic nobles. His title of elector of

the Palatinate was given to his distant cousin Duke

Maximilian of Bavaria.

Frederick, now landless, made himself a prominent exile abroad and tried to curry support for his cause in

Sweden,

Netherlands and

Denmark.

This was a serious blow to Protestant ambitions in the region. As the rebellion collapsed, the widespread confiscation of property and suppression of the

Bohemian nobility ensured that the country would return to the Catholic side after

more than two centuries of Hussite and other religious dissent. The Spanish, seeking to outflank the Dutch in preparation for renewal of the Eighty Years' War, took Frederick's lands, the Rhine Palatinate. The first phase of the war in eastern Germany ended 31 December 1621, when the Prince of Transylvania and the Emperor signed

the Peace of Nikolsburg, which gave

Transylvania a number of territories in

Royal Hungary.

Johan Tzerclaes, Count of Tilly, commander of the Bavarian and Imperial armies.

Johan Tzerclaes, Count of Tilly, commander of the Bavarian and Imperial armies.Some historians regard the period from

1621–1625 as a distinct portion of the

Thirty Years' War, calling it the "

Palatinate phase". With the catastrophic defeat of

the Protestant army at

White Mountain and the departure of the

Prince of Transylvania,

greater Bohemia was pacified. However, the war in the Palatinate continued: Famous mercenary leaders - such as, particularly, Count

Ernst von Mansfeld - helped

Frederick V to defend his countries,

the Upper and the Rhine Palatinate. This phase of the war consisted of much smaller battles, mostly sieges conducted by the Spanish army.

Mannheim and

Heidelberg fell in 1622, and

Frankenthal was taken two years later, thus

leaving the Palatinate in the hands of the Spanish.

The remnants of

the Protestant armies, led by Count

Ernst von Mansfeld and Duke

Christian of Brunswick, withdrew into

Dutch service. Although their arrival in

the Netherlands did help to lift the siege of

Bergen-op-Zoom (October 1622),

the Dutch could not provide permanent shelter for them. They were paid off and sent to occupy neighboring

East Friesland.

Mansfeld remained in

the Dutch Republic, but

Christian wandered off to "

assist" his kin in the

Lower Saxon Circle, attracting the attentions of

Tilly. With the news that

Mansfeld would not be supporting him,

Christian's army began a steady retreat toward the safety of

the Dutch border. On 6 August 1623,

Tilly's more disciplined army caught up with them 10 miles short of the Dutch border. The battle that ensued was known as

the Battle of Stadtlohn. In this battle

Tilly decisively defeated

Christian, wiping out over four-fifths of his army, which had been some 15,000 strong. After this catastrophe,

Frederick V, already in exile in

The Hague, and under growing pressure from his father-in-law

James I to end his involvement in the war, was forced to abandon any hope of launching further campaigns.

The Protestant rebellion had been crushed.

Huguenot rebellions (1620-1628) Count-Duke of Olivares, favourite and minister of Philip IV, painted by Diego Velázquez.

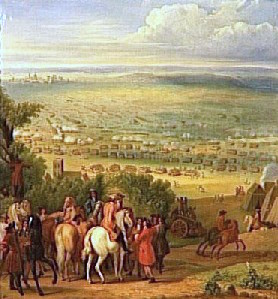

Count-Duke of Olivares, favourite and minister of Philip IV, painted by Diego Velázquez. Cardinal Richelieu at the Siege of La Rochelle against the Huguenots, Henri Motte, 1881.

Cardinal Richelieu at the Siege of La Rochelle against the Huguenots, Henri Motte, 1881.In

France, the

Protestant Huguenots, mainly located in the southwestern provinces, revolted against the

central Royal power of the French government. The uprising followed the death of

Henry IV, who, himself originally a

Huguenot before converting to

Catholicism, had protected

Protestants through

the Edict of Nantes. The new ruler however,

Louis XIII, under the regency of his Italian Catholic mother

Marie de' Medici, became more intolerant of

the Protestant religion. The

Huguenots tried to respond by defending themselves, establishing independent political and military structures, establishing diplomatic contacts with foreign powers, and openly revolting against central power. The Huguenot rebellions came after two decades of internal peace under

Henry IV, following the intermittent

French Wars of Religion of

1562–1598. The rebellion led to major military encounters, which ended in defeat for the

Huguenots:

the Siege of Montauban,

the Naval battle of Saint-Martin-de-Ré on 27 October 1622,

the Capture of Ré island in 1625, and

the Siege of La Rochelle in 1627-1628 which became an international conflict with the involvement of

England in

the Anglo-French War (1627-1629). The House of

Stuart in

England had been involved in attempts to secure peace in Europe (through the Spanish Match) and had intervened in

the 30 Years' War against both

Spain and

France. However, due in part to the scale of the defeat (which indirectly lead to the assassination of the English leader the

Duke of Buckingham), and also due to the lack of funds for war, which stemmed from internal conflict between

Charles I and

his Parliament,

England stopped being involved in European affairs, to the dismay of

Protestant forces on the continent.

France remained the largest Catholic kingdom that was not only not aligned with

the Habsburg powers but would come to actively wage war against

Spain. The French Crown's response to

the Hugeunot rebellion was not so much a representation of the typical religious polarisation of

the Thirty Years' War, but rather the attempts at achieving national hegemony by

absolutist monarchy.

Danish intervention (1625–1629) King Christian IV of Denmark, General of the Lutheran army.

King Christian IV of Denmark, General of the Lutheran army. Catholic General Albrecht von Wallenstein.

Catholic General Albrecht von Wallenstein.Peace in the Empire was short-lived, however, as conflict resumed at the initiation of

Denmark. Danish involvement, referred to as

Low Saxon War or Kejserkrigen ("Emperor's War"), began when

Christian IV of Denmark, a Lutheran who was also the

Duke of Holstein, a duchy within the Holy Roman Empire, helped

the Lutheran rulers of neighbouring

Lower Saxony by leading an army against the Imperial forces.

Denmark had feared that its sovereignty as a Protestant nation was threatened by the recent Catholic successes.

Christian IV had also profited greatly from his policies in

northern Germany. For instance, in 1621,

Hamburg had been forced to accept

Danish sovereignty and Christian's second son was made bishop of

Bremen.

Christian IV had obtained for his kingdom a level of stability and wealth that was virtually unmatched elsewhere in Europe. This stability and wealth was paid for by tolls on the

Oresund and also by extensive war reparations from

Sweden.

Denmark's cause was aided by

France which, together with

England, had agreed to help subsidize the war.

Christian had himself appointed war leader of

the Lower Saxon Circle and raised an army of 20,000 mercenaries and a national army 15,000 strong.

To fight him,

Ferdinand II employed the military help of

Albrecht von Wallenstein, a Bohemian nobleman who had made himself rich from the confiscated estates of his countrymen.

Wallenstein pledged his army, which numbered between 30,000 and 100,000 soldiers, to

Ferdinand II in return for the right to plunder the captured territories.

Christian, who knew nothing of

Wallenstein's forces when he invaded, was forced to retire before the combined forces of

Wallenstein and

Tilly.

Christian's poor luck was with him again when all of the allies he thought he had were forced aside:

England was weak and internally divided,

France was in the midst of a civil war,

Sweden was at war with

the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, and neither

Brandenburg nor

Saxony were interested in changes to the tenuous peace in

eastern Germany.

Wallenstein defeated

Mansfeld's army at

the Battle of Dessau Bridge (1626) and General

Tilly defeated

the Danes at

the Battle of Lutter (1626).

Mansfeld died some months later of illness, apparently tuberculosis, in

Dalmatia.

Wallenstein's army marched north, occupying

Mecklenburg,

Pomerania, and ultimately

Jutland itself. However, he was unable to take the Danish capital on the island of

Zealand.

Wallenstein lacked a fleet, and neither the Hanseatic ports nor the Poles would allow an Imperial fleet to be built on the Baltic coast. He then laid siege to

Stralsund, the only belligerent Baltic port with the facilities to build a large fleet. However, the cost of continuing the war was exorbitant compared to what could possibly be gained from conquering the rest of

Denmark.

Wallenstein feared to lose his

North German gains to a

Danish-Swedish alliance, and

Christian IV had suffered another defeat in

the Battle of Wolgast, so both were ready to negotiate.

Negotiations were concluded with

the Treaty of Lübeck in 1629, which stated that

Christian IV could keep his control over

Denmark if he would abandon his support for

the Protestant German states. Thus, in the following two years more land was subjugated by

the Catholic powers. At this point,

the Catholic League persuaded

Ferdinand II to take back

the Lutheran holdings that were, according to

the Peace of Augsburg, rightfully the possession of

the Catholic Church. Enumerated in

the Edict of Restitution (1629), these possessions included two Archbishoprics, sixteen bishoprics, and hundreds of monasteries. The same year,

Gabriel Bethlen, the Calvinist Prince of

Transylvania, died. Only the port of Stralsund continued to hold out against Wallenstein and the Emperor.

Swedish intervention (1630–1635) Cardinal-Infante Ferdinand of Spain, commander of the Spanish and Imperial armies.

Cardinal-Infante Ferdinand of Spain, commander of the Spanish and Imperial armies. The Battle of Breitenfeld (1631)

The Battle of Breitenfeld (1631)Some within

Ferdinand II's court did not trust

Wallenstein, believing that he sought to join forces with

the German Princes and thus gain influence over the Emperor.

Ferdinand II dismissed

Wallenstein in 1630. He was to later recall him after the Swedes, led by King

Gustaf II Adolf (Gustavus Adolphus), had invaded the Holy Roman Empire with success and turned the tables on the Catholics. His contributions made

Sweden the continental leader of

Protestantism until the Swedish Empire ended in 1721.

Gustavus Adolphus, like

Christian IV before him, came to aid the

German Lutherans, to forestall Catholic aggression against their homeland, and to obtain economic influence in the German states around the Baltic Sea. In addition,

Gustavus was concerned about the growing power of

the Holy Roman Empire. No one knows the exact reason for

Gustavus to enter the war and this has been widely argued. Like

Christian IV,

Gustavus Adolphus was subsidized by

Cardinal Richelieu, the Chief Minister of

Louis XIII of

France, and by

the Dutch. From 1630 to 1634, Swedish-led armies drove the Catholic forces back, regaining much of the lost Protestant territory. During his campaign he managed to conquer half of the Imperial kingdoms.

Swedish forces entered the Holy Roman Empire via the Duchy of

Pomerania, which served as the Swedish bridgehead since

the Treaty of Stettin (1630). After dismissing

Wallenstein in 1630,

Ferdinand II became dependent on

the Catholic League.

Gustavus Adolphus allied with

France in

the Treaty of Bärwalde (January 1631).

France and

Bavaria signed

the secret Treaty of Fontainebleau (1631), but this was rendered irrelevant by Swedish attacks against

Bavaria. At

the Battle of Breitenfeld (1631),

Gustavus Adolphus's forces defeated the Catholic League led by

General Tilly. A year later they met again in another Protestant victory, this time accompanied by the death of

Tilly. The upper hand had now switched from the league to the union, led by

Sweden. In 1630,

Sweden had paid at least 2,368,022 daler for its army of 42,000 men. In 1632, it contributed only one-fifth of that (476,439 daler) towards the cost of an army more than three times as large (149,000 men). This was possible due to subsidies from

France, and the recruitment of prisoners (most of them taken at

the Battle of Breitenfeld) into the Swedish army. The majority of mercenaries recruited by

Gustavus II Adolphus were German but Scottish mercenaries were also common. With

Tilly dead,

Ferdinand II returned to the aid of

Wallenstein and his large army.

Wallenstein marched up to the south, threatening

Gustavus Adolphus's supply chain.

Gustavus Adolphus knew that

Wallenstein was waiting for the attack and was prepared, but found no other option.

Wallenstein and

Gustavus Adolphus clashed in

the Battle of Lützen (1632), where the

Swedes prevailed, but

Gustavus Adolphus was killed.

Ferdinand II's suspicion of

Wallenstein resumed in 1633, when

Wallenstein attempted to arbitrate the differences between the

Catholic and

Protestant sides.

Ferdinand II may have feared that

Wallenstein would switch sides, and arranged for his arrest after removing him from command. One of Wallenstein's soldiers,

Captain Devereux, killed him when he attempted to contact the Swedes in the town hall of Eger (Cheb) on 25 February 1634. The same year, the Protestant forces, lacking Gustav's leadership, were defeated at

the First Battle of Nördlingen by the Spanish-Imperial forces commanded by

Cardinal-Infante Ferdinand.

The victory of Gustavus Adolphus at the Battle of Breitenfeld (1631).

The victory of Gustavus Adolphus at the Battle of Breitenfeld (1631).By the Spring of 1635, all Swedish resistance in the south of

Germany had ended. After that, the two sides met for negotiations, producing

the Peace of Prague (1635), which entailed a delay in the enforcement of

the Edict of Restitution for 40 years and allowed Protestant rulers to retain secularized bishoprics held by them in 1627. This protected

the Lutheran rulers of northeastern Germany, but not those of the south and west (whose lands had been occupied by the Imperial or League armies prior to 1627).

The treaty also provided for the union of the army of the Emperor and the armies of the German states into a single army of the Holy Roman Empire (although Johann Georg of Saxony and Maximillian of Bavaria kept, as a practical matter, independent command of their forces, now nominally components of the "Imperial" army). Finally, German princes were forbidden from establishing alliances amongst themselves or with foreign powers, and amnesty was granted to any ruler who had taken up arms against the Emperor after the arrival of the Swedes in 1630.

This treaty failed to satisfy France, however, because of the renewed strength it granted the Habsburgs. France then entered the conflict, beginning the final period of the Thirty Years' War.

French intervention (1635–1648) Although a Catholic clergyman himself, Cardinal Richelieu allied France with the Protestants.

Although a Catholic clergyman himself, Cardinal Richelieu allied France with the Protestants. The Battle of Lens, 1648. Torstenson 1642

The Battle of Lens, 1648. Torstenson 1642France, although Roman Catholic, was a rival of the Holy Roman Empire and Spain. Cardinal Richelieu, the Chief Minister of King Louis XIII of France, felt that the Habsburgs were too powerful, since they held a number of territories on France's eastern border, including portions of the Netherlands. Richelieu had already begun intervening indirectly in the war in January 1631, when the French diplomat Hercules de Charnace signed the Treaty of Bärwalde with Gustavus Adolphus, by which France agreed to support the Swedes with 1,000,000 livres each year in return for a Swedish promise to maintain an army in Germany against the Habsburgs. The treaty also stipulated that Sweden would not conclude a peace with the Holy Roman Emperor without first receiving France's approval.

After the Swedish rout at Nördlingen in September 1634 and the Peace of Prague in 1635, as Sweden's ability to continue the war alone appeared doubtful, Richelieu made the decision to enter into direct war against the Habsburgs. France declared war on Spain in May 1635 and the Holy Roman Empire in August 1636, opening offensives against the Habsburgs in Germany and the Low Countries. France aligned her strategy with the allied Swedes in Wismar (1636) and Hamburg (1638).

French military efforts met with disaster, and the Spanish counter-attacked, invading French territory. The Imperial general Johann von Werth and Spanish commander Cardinal-Infante Ferdinand of Spain ravaged the French provinces of Champagne, Burgundy and Picardy, and even threatened Paris in 1636 before being repulsed by Bernhard of Saxe-Weimar. Bernhard's victory in the Battle of Compiègne pushed the Habsburg armies back towards the borders of France. Widespread fighting ensued, with neither side gaining an advantage. In 1642, Cardinal Richelieu died. A year later, Louis XIII died, leaving his five-year-old son Louis XIV on the throne. His chief minister, Cardinal Mazarin, facing the domestic crisis of the Fronde in 1645, began working to end the war.

In 1643, the Swedish marshal Lennart Torstenson expelled Danish prince Frederick from Bremen-Verden, gaining a stronghold south of Denmark and hindering Danish participation as mediatiors in the peace talks in Westphalia.[42] In 1645, Torstenson defeated the Imperial army at the Battle of Jankau near Prague, and Louis II de Bourbon, Prince de Condé defeated the Bavarian army in the Second Battle of Nördlingen. The last Catholic commander of note, Baron Franz von Mercy, died in the battle.

On 14 March 1647

Bavaria,

Cologne,

France and

Sweden signed

the Truce of Ulm. In 1648 the Swedes (commanded by Marshal Carl Gustaf Wrangel) and the French (led by Turenne and Condé) defeated the Imperial army at the Battle of Zusmarshausen and Lens. These results left only the Imperial territories of Austria safely in Habsburg hands.

Peace of WestphaliaFrench General Louis II de Bourbon, 4th Prince de Condé, Duc d'Enghien, The Great Condé defeated the Spanish at the Battle of Rocroi in 1643, which led to negotiations. Over a four year period, the parties were actively negotiating at Osnabrück and Münster in Westphalia. The end of the war was not brought about by one treaty but instead by a group of treaties such as the Treaty of Hamburg. On 15 May 1648, the Treaty of Osnabrück was signed. Over five months later, on 24 October, the Treaty of Münster was signed, ending both the Thirty Years' War and the Eighty Years' War.

Casualties and diseaseSo great was the devastation brought about by the war that estimates put the reduction of population in the German states at about 15% to 30%. Some regions were affected much more than others. For example, Württemberg lost three-quarters of its population during the war. In the territory of Brandenburg, the losses had amounted to half, while in some areas an estimated two-thirds of the population died. The male population of the German states was reduced by almost half. The population of the Czech lands declined by a third due to war, disease, famine and the expulsion of Protestant Czechs. Much of the destruction of civilian lives and property was caused by the cruelty and greed of mercenary soldiers, many of whom were rich commanders and poor soldiers. Villages were especially easy prey to the marauding armies. Those that survived, like the small village of Drais near Mainz would take almost a hundred years to recover. The Swedish armies alone may have destroyed up to 2,000 castles, 18,000 villages and 1,500 towns in Germany, one-third of all German towns. The war caused serious dislocations to both the economies and populations of central Europe, but may have done no more than seriously exacerbate changes that had begun earlier.

Pestilence of several kinds raged among combatants and civilians in Germany and surrounding lands from 1618 to 1648. Many features of the war spread disease. These included troop movements, the influx of soldiers from foreign countries, and the shifting locations of battle fronts. In addition, the displacement of civilian populations and the overcrowding of refugees into cities led to both disease and famine. Information about numerous epidemics is generally found in local chronicles, such as parish registers and tax records, that are often incomplete and may be exaggerated. The chronicles do show that epidemic disease was not a condition exclusive to war time, but was present in many parts of Germany for several decades prior to 1618.

However, when the Danish and Imperial armies met in

Saxony and

Thuringia during 1625 and 1626,

disease and

infection in local communities increased. Local chronicles repeatedly referred to "

head disease", "

Hungarian disease", and a "

spotted" disease identified as

typhus. After

the Mantuan War, between

France and

the Habsburgs in

Italy, the

northern half of the Italian peninsula was in the throes of a

bubonic plague epidemic. During the unsuccessful siege of

Nuremberg, in 1632, civilians and soldiers in both the Swedish and Imperial armies succumbed to typhus and scurvy. Two years later, as the Imperial army pursued the defeated Swedes into southwest

Germany, deaths from epidemics were high along the

Rhine River. Bubonic plague continued to be a factor in the war. Beginning in 1634,

Dresden,

Munich, and smaller German communities such as

Oberammergau recorded large numbers of

plague casualties. In the last decades of the war, both typhus and dysentery had become endemic in

Germany.

Political consequences Damages in Germany's population as percentupload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/7d/Holy_Roman_Empire_1648.svgCentral Europe at the end of the Thirty Years' War, showing the fragmentation that resulted in decentralization.

Damages in Germany's population as percentupload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/7d/Holy_Roman_Empire_1648.svgCentral Europe at the end of the Thirty Years' War, showing the fragmentation that resulted in decentralization.One result of the war was the division of Germany into many territories — all of which, despite their membership in the Empire, won de facto sovereignty. This limited the power of the Holy Roman Empire and decentralized German power.

The Thirty Years' War rearranged the European power structure.

The conflict made Spain's military and political decline visible. While

Spain was fighting in

France,

Portugal — which had been under personal union with

Spain for 60 years — acclaimed

John IV of

Braganza as king in 1640, and the

House of Braganza became

the new dynasty of Portugal. Meanwhile,

Spain was forced

to accept the independence of the Dutch Republic in 1648, ending the Eighty Years' War.

France gradually began to replace a weakening

Spain in influence, beginning with

the Franco-Spanish War (1635-59) and confirmed by

the War of Devolution and

the Franco-Dutch War. Even before the last three decades of the century, it was undeniable that

Bourbon France, under the leadership of

Louis XIV, had surpassed a declining

Habsburg Spain as Europe's leading power.

Louis XIV, le Roi Soleil, le Grand

Louis XIV, le Roi Soleil, le GrandFrom 1643–45, during the last years of

the Thirty Years' War,

Sweden and

Denmark fought the Torstenson War. The result of that conflict and the conclusion of the great European war at

the Peace of Westphalia in 1648 helped establish

post-war Sweden as a force in Europe.

Lennart Torstenson, Count of Ortala, Baron of Virestad (17 August 1603 – 7 April 1651), was a Swedish Field Marshal and military engineer.

Lennart Torstenson, Count of Ortala, Baron of Virestad (17 August 1603 – 7 April 1651), was a Swedish Field Marshal and military engineer.The edicts agreed upon during the signing of

the Peace of Westphalia were instrumental in laying the foundations for what are even today considered the basic tenets of the sovereign nation-state. Aside from establishing fixed territorial boundaries for many of the countries involved in the ordeal (as well as for the newer ones created afterwards),

the Peace of Westphalia changed the relationship of subjects to their rulers. In earlier times, people had tended to have overlapping political and religious loyalties. Now, it was agreed that the citizenry of a respective nation were subjected first and foremost to the laws and whims of their own respective government rather than to those of neighboring powers, be they religious or secular.

The war also has a few more subtle consequences.

The Thirty Years' War marked the last major religious war in mainland Europe, ending the large-scale religious bloodshed accompanying

the Reformation, in 1648. There were other religious conflicts in the years to come, but no great wars. Also, the destruction caused by mercenary soldiers defied descriptio. The war did much to end the age of mercenaries that had begun with the first Landsknechts, and ushered in the age of well-disciplined national armies.

The war also had consequences abroad, as the European powers extended their fight via naval power to overseas colonies.

In 1630, a Dutch fleet of 70 ships had taken the rich sugar-exporting areas of Pernambuco (Brazil) from the Portuguese but had lost everything by 1654. Fighting also took place in

Africa and

Asia.