|

|

Post by pieter on Aug 10, 2014 12:02:03 GMT -7

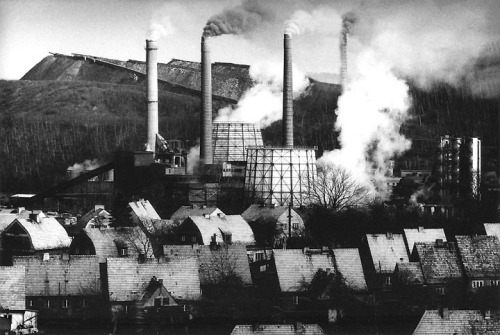

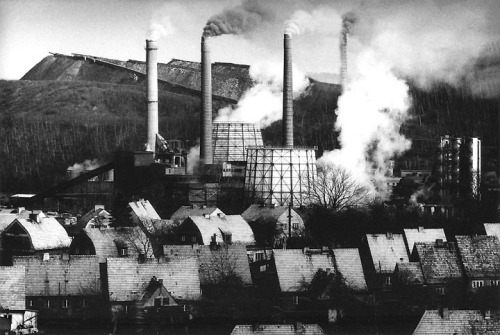

Karl, You are welcome. I hope that you can enjoy the images as an interested neighbor and friend. As someone with a photographic training and background. I think that we have to realize and accept the fact that Poland is not only portrayed by Polish photographers, filmers (moviemakers), aritsts and writers, but also by outsiders. Germans, Danes, Americans, Czechs, Slovaks, Russians, Dutch people who visited it. I learned a lot about Poland by reading the stuf foreign visitors wrote about it. Sometimes an outsider or someone with a non-Polish background has the fresh look of an anthropologist, historian, research journalist or just a curious artist. So also between the images I collected here about Poland there will be images of non-Poles. Ofcourse the Polish artists, photographers, students and just people who took images of their family lives, friends, colleages or strangers on the street or in the countryside, documented and illustrated Polish history and the Poland of the 20th century through their lens. I have to say with my old fashionate taste (maybe) I love and loved all the old analogue quality images of Poland. I enjoyed both the professional and the amateur images. Due to the low fi quality of the amateur images you feel connected, because in the images you see your own family background, the images of my own families holidays in Poland. The Amateur photograph image of Warsaw, 1987 with the old lady with the beige jacket and the people with the blue coats in the background remind me of family photo albums of my own family. I love some of the black and white photographs for their quintessence, and for their nearly abstract quality. (Bytom, szombierki, ulica zabrzanska, silesia, poland, 1985)  Amateur photograph image of Warsaw, 1987 Amateur photograph image of Warsaw, 1987 Bytom, szombierki, ulica zabrzanska, silesia, poland, 1985 Bytom, szombierki, ulica zabrzanska, silesia, poland, 1985Next to the photographic memories about the journey's and stay's in Poland of the seventies, eighties, 2004 and 2006, I remember the smell, sounds, atmosphere, people, the things that happened during our stay there. That flavor of life you can't catch in a photograph, filmstill, movie, drawing or painting. The view of your real eyes (your personal life camera) and memory can't be beaten by the photocamera or movie camera. Imagine your own photo's of Denmark, Germany, South-Africa, Namibia, Syria, Seattle, Uruguay, Argentine and Mexico today. Your color negatives and slides of all those places that meant something to your life. Maybe you don't have images of the first stage of your life in Denmark, maybe photography started for you in Germany. But how vividly you described your boyhood/childhood time, created photographic or filmstill like images in my head. Ofcourse of my own fantasy and interpretation. But stil your stories did. And what your eyes, senses and brains recorder back then stil is stored somewhere in your memory. Our past was segregated by a few hundred kilometers of space and a few decades of time, but we have similarities in the European experience, coming from the same corner of Europe (Like John visiting Vermont, coming from New Hampshire. The Netherlands and Northern-Germany are the mirror image of New England, situated in the Washington state area of North-West Europe. If New Hampshire is the Netherlands, Vermont is the North-Germany and Denmark of the North-East of the States) You had the fortune to visit, stay in and work in those countries and examin and experience those places as an outsider, who for short periods was allowed to look at those places as an insider. Because you were as a professional there, not as some tourists. So you were allowed to learn about those countries, to get to know the people, get used to the landscapes and cultures, the atmospheres, religions, ethnic particularities, heritages and differences with the Europe you came from. Poland for me was both alien, exotic, different and exiting. Different from the world, the society, the language, people and system I knew as a child. The Netherlands was a completely different world than Poland in the seventies and eighties. The difference created for me the circumstances to investigate, to explore, research, observe, analyse and experience. I watched, watched and watched and participated by being there. The language was alien to me so I was dependent of my parents, grandparents, uncles and aunts and their relatives and friends. I always kept that double feeling about Poland, which is a bit alienating. From one side I am an alien, an outsider, a voyeur, an explorer, and even partly a tourist over there (something I hate to admid), and from the other side I am at home there. There is a familybranch there, there are roots there and there is something like what you are having when you are in Denmark. I had no choice and was made a Dutchman, you were transformed from a Frisian boy from Denmark to a German. We are both loyal to our states/countries, but feel a special connection to the birthplace of our mother and the family and people of their nations. For me part of the connection to Poland is by doing something with it. I have to read about it, made images there (Photography), read Polish authors, and follow English language, German and Dutch language news about Poland. There is not extremely much news about Poland in those languages, but the news I get I read, view and digest. More important is to go back to make connection with people of that country when I have the chance to. I have a lot still to explore about Poland. Haven't seen a lot of cities and towns yet. I am curious about landscapes, mountains and lake area's I haven't seen yet, and with my North-sea coastal background it would be nice to see the Baltic coast sometimes. I am especially interested in the larger Polish cities. Szczecin ( Stettin) and Wrocław ( Breslau) with their German roots and Polish present, Łódź with it's interesting history, cultural meaning and central location in Poland. Bydgoszcz as one of the major cultural centers in the country. Lublin as an interesting old city, Białystok as Poland's largest city in the East, with a lot of Central- and Eastern-European influences. Internet and the huge amount of photo's about Poland give me an impression of the country. It will be interesting to see the organic growth of these cities, with historical architectonic layers and elements (Romanesque, Polish gothic, Italian Renaissance, Bohemian influences, the elements the German and Dutch burghers of the Polish towns, the baroque and rococo styles, the classicism and symbolism of the 19th century, and the Jugendstil and Art nouveau of the the early 20th century, and the Modernism after that, and the communist architecture of the cold war). Polish towns and cities are exiting and interesting due to the layers of history in it. The past, present and future makes these cities exiting. And visiting Poland today might be a very interesting experience, because you enter the future, with it's modern infrastructure (highways, roads, new railways), new architecture and skylines of cities, the new digital infrastructure and the mix of Polish and Western-European, American and Asian (Chinese, Japanese, Korean and other imported products, like cars, consumer products, advertisements and etc.) influences, also due to the presence of Vietnamese and Chinese ethnic minorities. I am very curious also how Poznań, Warsaw and Kraków will look today. What is changed and what has stayed the same?  Łódź skyline Łódź skylineThis particular and wonderful thread created by Jaga, is very important and dear to me. For me watching and reading these kind of topics is a roots and heritage thing for me. That's why I love this Forum and the other Forum (Bononobo's Polish Culture Forum). The invaluable value of the historical, photographic and cultural subjects, topics and items are very important to me. It's my connection to the heritage. And I am sure the same thing counts for other individuals with partly Polish heritage. The other people of the Polish diaspora and Polonia who visit these Forums and Polish culture websites. It connects me to the Motherland, while living in the fatherland literary! So, Jaga and Bonobo are important people to me and others. I am very grateful for your work and effort Jaga! Cheers, Pieter |

|

|

|

Post by pieter on Aug 12, 2014 5:41:57 GMT -7

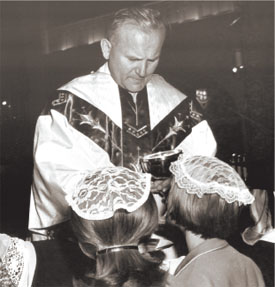

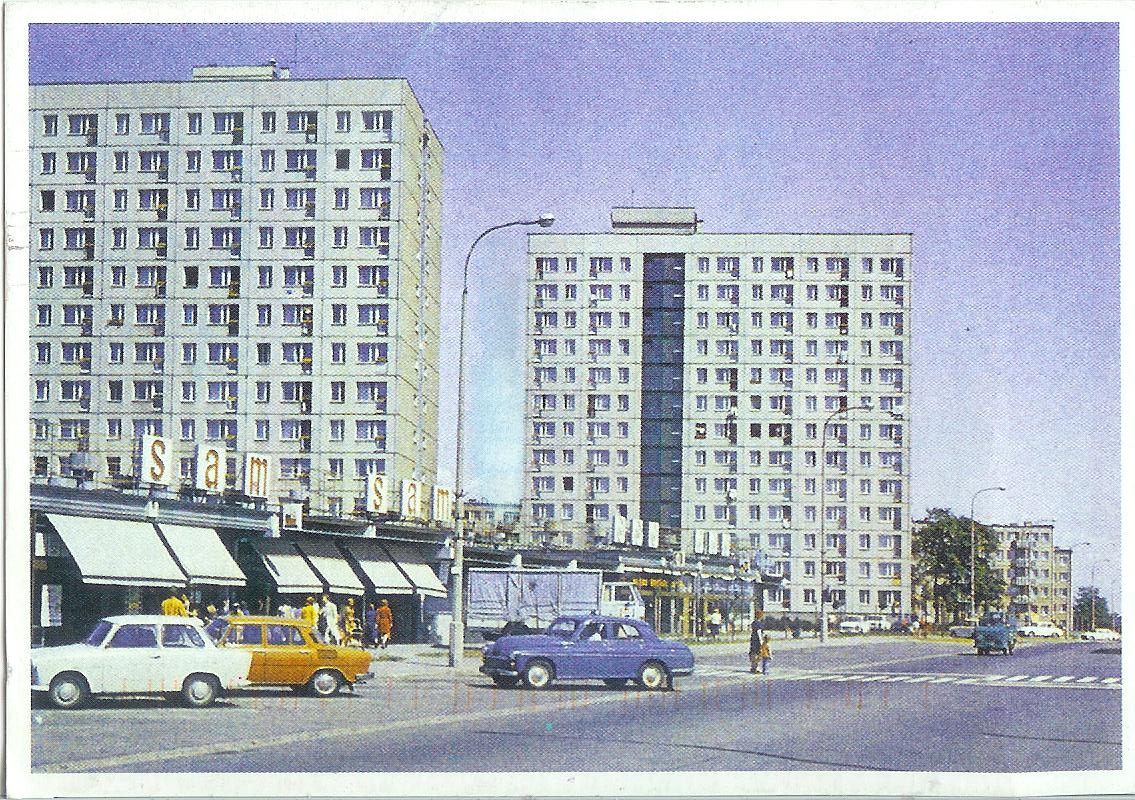

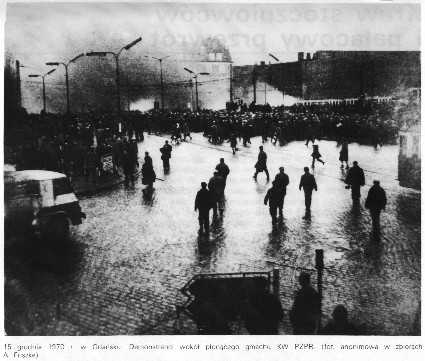

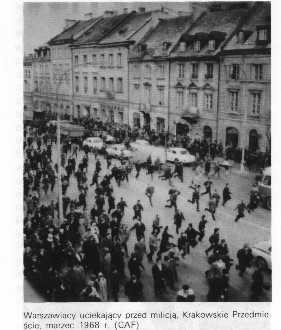

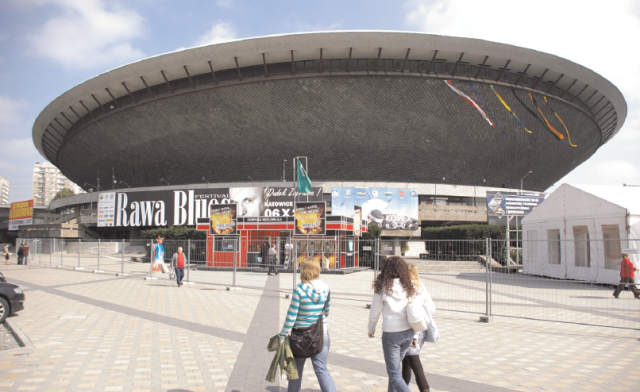

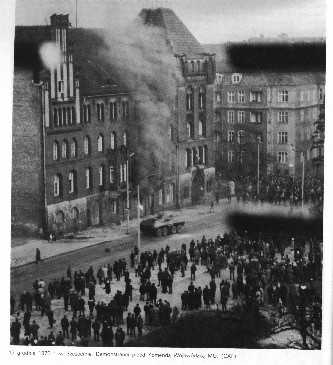

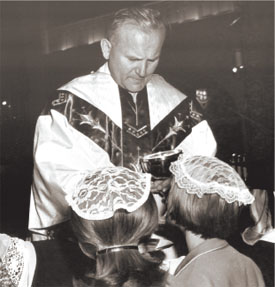

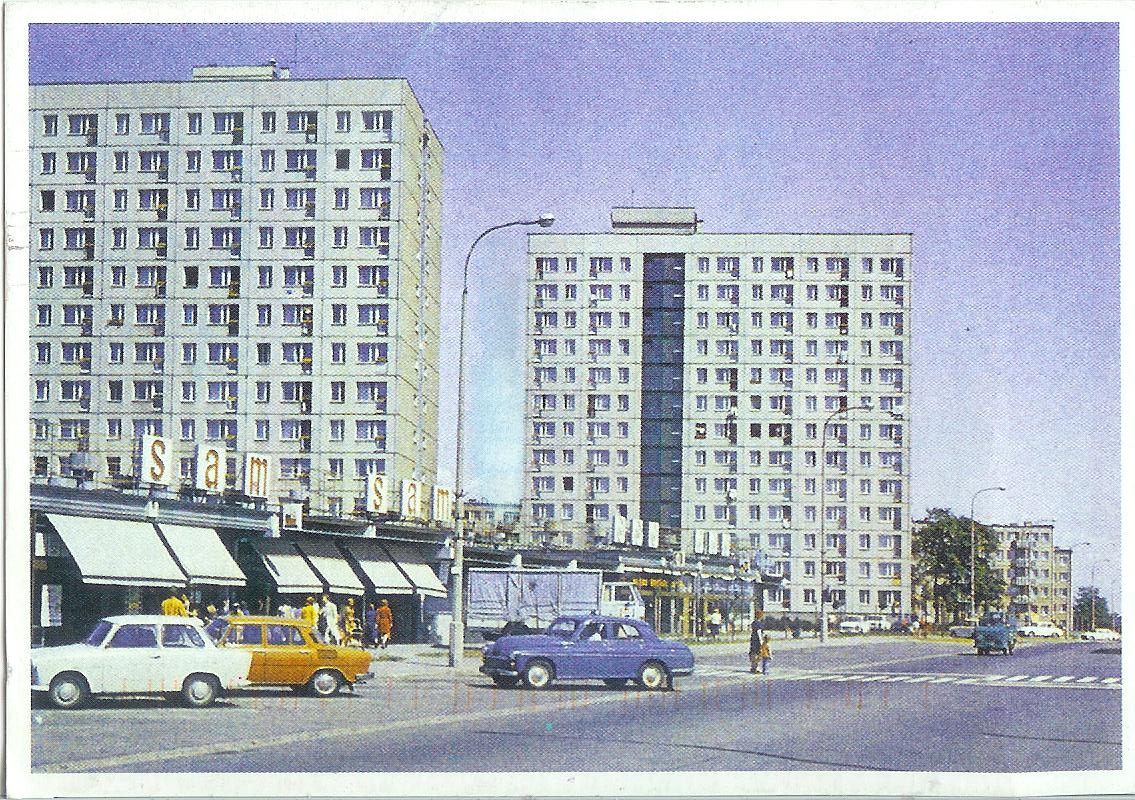

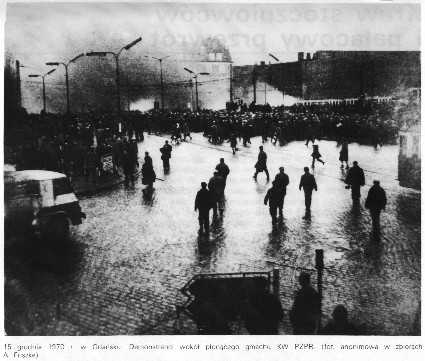

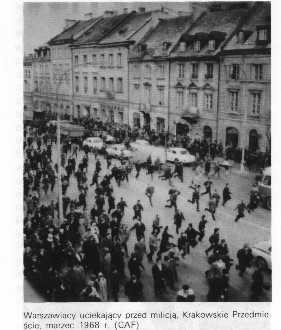

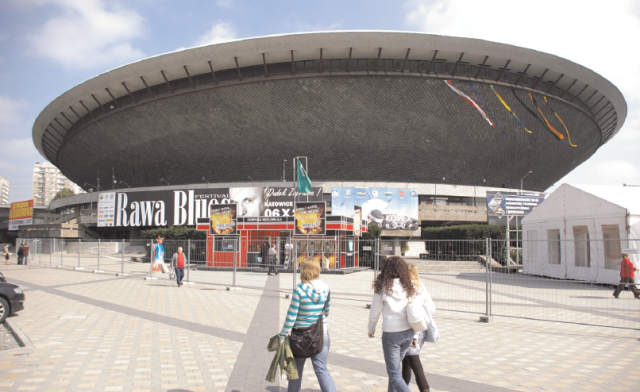

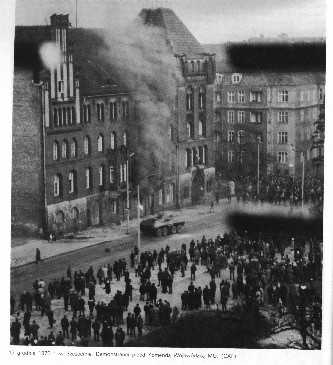

Communists in 1970    The anti-communist opposition in 1970 The anti-communist opposition in 1970 Gdansk,December 15, 1970 [from Andrzej Friszke, Polska Gierka, [Gierek's Poland, Warsaw, 1995]. Gdansk,December 15, 1970 [from Andrzej Friszke, Polska Gierka, [Gierek's Poland, Warsaw, 1995]. Students fleeing from militia, Krakowskie Przedmiescie street, Warsaw, March 1968 [from: Pawel Machcewicz, Wladyslaw Gomulka, Warsaw,1995]. Students fleeing from militia, Krakowskie Przedmiescie street, Warsaw, March 1968 [from: Pawel Machcewicz, Wladyslaw Gomulka, Warsaw,1995]. Polish 1970 protests - Zbyszek Godlewski body Polish 1970 protests - Zbyszek Godlewski body Architecture and the Image of the Future in the People's Republic of Poland. Architecture and the Image of the Future in the People's Republic of Poland. Nowadays 1 May is still celebrated by a few dozen thousand veterans of communist movement, current leftist activists, trade unionists and all people who believe in socialist ideals all over Poland.   December ’70 in Szczecin December ’70 in Szczecin The PZPR Communist party headquarters in flames, Szczecin, December 17th, 1970 The PZPR Communist party headquarters in flames, Szczecin, December 17th, 1970 The PZPR Communist party headquarters in flames, Szczecin, December 17th, 1970 The PZPR Communist party headquarters in flames, Szczecin, December 17th, 1970On December 17th, 1970, a crowd of 20,000 striking shipyard workers and ordinary Szczecinians registered their displeasure at rising food prices, and a massacre of workers in Gdynia earlier in the day, by burning down the headquarters of the local P.Z.P.R. Communist party.  PZPR building in flames, 17th December, 1970 PZPR building in flames, 17th December, 1970 PZPR building in flames, 17th December, 1970 PZPR building in flames, 17th December, 1970 During "Black Thursday", the tragic Polish workers riots of December 1970, many workers lost their lives.The Party, PZPR During "Black Thursday", the tragic Polish workers riots of December 1970, many workers lost their lives.The Party, PZPR Communist Party leaders adress a crowd Communist Party leaders adress a crowd    Polish militia man with a child holding a Sovjet flag Polish militia man with a child holding a Sovjet flag      Classics of Polish cinema – ‘Rejs’ Classics of Polish cinema – ‘Rejs’Rejs shows the peculiar Polish flavour of communism in the People’s Republic, where by 1970 there was very little terror and repression, but rather boredom, bureaucracy and inefficiency; the country itself was like a ship drifting aimlessly, with the wrong people in charge, and the passengers forced to play out an absurd pantomime.    Polski Fiat 125p Poland 1969 (green) Polski Fiat 125p Poland 1969 (green).jpg) Warsaw of 1969 in Color Warsaw of 1969 in Color .jpg) Warsaw of 1969 in Color Warsaw of 1969 in Color .jpg) Warsaw of 1969 Warsaw of 1969.jpg) Warsaw of 1969 Warsaw of 1969.jpg) Warsaw of 1969 Warsaw of 1969.jpg) Warsaw of 1969 Warsaw of 1969.jpg) Warsaw of 1969 Warsaw of 1969.jpg) Warsaw of 1969 Warsaw of 1969.jpg) Warsaw of 1969 Warsaw of 1969.jpg) Warsaw of 1969 Warsaw of 1969  Fr. Philip Majka (right), a priest of the Richmond Diocese at the time, escorts Cardinal Karol Wojtyla of Krakow, Poland, around Washington, D.C., in 1969. Fr. Philip Majka (right), a priest of the Richmond Diocese at the time, escorts Cardinal Karol Wojtyla of Krakow, Poland, around Washington, D.C., in 1969. Wojtila in Rome in 1968 Wojtila in Rome in 1968 BUFFALO 1969. Archbishop Karol Wojtyla of Krakow visited Western New York in 1969 and again in 1976. He is shown here meeting children of the Millennium School at the Peace Bridge. Providing the Guard of Honor is Karol Tomaszewski, commander of Post 33, Polish Veterans of World War II. BUFFALO 1969. Archbishop Karol Wojtyla of Krakow visited Western New York in 1969 and again in 1976. He is shown here meeting children of the Millennium School at the Peace Bridge. Providing the Guard of Honor is Karol Tomaszewski, commander of Post 33, Polish Veterans of World War II.  Cardinal Karol Wojtilla visit to Cleveland in 1969 Cardinal Karol Wojtilla visit to Cleveland in 1969 Karol Wojtyla and Pope Paul VI Karol Wojtyla and Pope Paul VI  A young Wojtyla, a young Bishop A young Wojtyla, a young Bishop

|

|

|

|

Post by pieter on Aug 12, 2014 8:23:36 GMT -7

Woman with two children and a Polski Fiat 125p, August 1979 Woman with two children and a Polski Fiat 125p, August 1979 Two older farmer women, Nowy Targ, Poland 1979 Two older farmer women, Nowy Targ, Poland 1979  Former inmate of the Nazi concentration camp at Auschwitz-Birkenau, Poland, gazes down at the ruins of gas chambers at the Auschwitz concentration camp in 1979 Former inmate of the Nazi concentration camp at Auschwitz-Birkenau, Poland, gazes down at the ruins of gas chambers at the Auschwitz concentration camp in 1979 BONEY M - LIVE IN POLAND 1979 DVD rare concert BONEY M - LIVE IN POLAND 1979 DVD rare concert I pilgrimage of Pope John Paul II to Poland (1979) I pilgrimage of Pope John Paul II to Poland (1979) Polish industry 1979 Polish industry 1979 Camera Buff (Poland – 1979) Camera Buff (Poland – 1979) Krakow, Poland circa 1978. — Zbigniew Bzdak Krakow, Poland circa 1978. — Zbigniew Bzdak Four people on a city street. Food crisis. Poland, 1978 Four people on a city street. Food crisis. Poland, 1978 The Old Market Square in Warsaw Poland The Old Market Square in Warsaw Poland Royal Castle under reconstruction, Warsaw, Poland, 1977  Farm yard with horses and carriage, Poland, 1977  Market square, Old town, Warsaw, Poland, 1977  President Jimmy Carter and Edward Gierek in 1977  View of the Great October Estate, 1977. Poznań, Poland  Poznań, 1977 Poznań, 1977 Tramwaje w Poznaniu, Poznań - 1977 rok, stare zdjęcia  Probably 'MTT Poznań' in May 1973 Probably 'MTT Poznań' in May 1973 |

|

|

|

Post by Jaga on Aug 12, 2014 23:27:11 GMT -7

Pieter,

I had tears in my eyes watching some of the pictures. Boney M was very popular in Poland, but they played their music on the concerts from the playback sometimes. I remember they were in Krakow, my classmate went there, I was sceptical since I thought it was a farce.

|

|

|

|

Post by pieter on Aug 13, 2014 2:26:08 GMT -7

Jaga,

It is very understandable that the images caused some emotions in you as a person. Because some of the images have intense historical, human and personal value. You were born and raised in Poland. Lived, studied and worked there as a kid, teenager and young adult. You feel connected to Kraków and Poland. The Polish Peoples Republic was your home country. These images give a short impression about life in that country in that period of time in a world that was different than today.

I agree with you that Boney M was a little bit a farce. Their real music was nice for the entertainment and dance quality of it. But they have never been my favorite. They lacked the quality of Earth, Wind & Fire, The Pointer Sisters, Donna Summer, Diana Ross, Stevie Wonder and The Jackson 5.

I am very greatful and happy that all those wonderful, excellent and dedicated professional and amateur photographers made those great photographs of the Polish peoples republic during the sixties, seventies and eighties. They show the Poland I saw as a kid and teenager, and the Poland you experienced as a child, teenage girl and young woman.

Cheers,

Pieter

P.S.- I hope that some of the more political images didn't hurt your feelings or caused sadness or pain. Because it could be tears of sadness, longing, but also of pain. I hope the tears were caused by good emotions. A melancholic or nostalgic Polish feeling?

|

|

|

|

Post by pieter on Aug 13, 2014 2:31:51 GMT -7

For people who wanted to feel and experience the Polish Peoples Republic times of communist Poland there was a museum in Kraków about it. PRL Museum The PRL Museum The PRL Museum (Polish: Muzeum PRL-u) was a museum in Kraków, Poland devoted to documenting the forty-year history of the pro-communist People's Republic of Poland (PRL). It occupied the building of the old Kino Światowid ("Svetovid Cinema"), a formerly state-owned cinema in the Nowa Huta district of Kraków.    The museum was established in 2008 as a division of the Warsaw Museum of Polish History. However, on November 7, 2012, the city council of Kraków decided to establish an independent museum in its place run by the city itself. The division of Warsaw Museum is now closed, and the museum building is scheduled to house the new Kraków Museum of PRL with similar focus, but with different administrative structure.  |

|

|

|

Post by pieter on Aug 13, 2014 3:37:07 GMT -7

New Polish Cinema New Polish Cinema Krystyna Janda and Adam Ferency, still form "Interrogation, photo: East News / PolfilmI. The Communist Era Krystyna Janda and Adam Ferency, still form "Interrogation, photo: East News / PolfilmI. The Communist EraIf we look at the films made in the Polish People's Republic without prejudices (we have the right to do so now more than ever), it turns out that the particular flavour of this cinema lies in the overwhelming presence of politics and artistic ambition. Without judging whether the Polish specificity was indeed an affliction of the whole cultural region of Eastern and Central Europe that was scooped up by the Soviet system after 1945, or if it had a deeper meaning that reaches back into the 19th century tradition of dealing with enslavement by means of culture, I advance the thesis that these two points are key indicators that define the 'essence' of the Polish cinema of that period. Describing them can help us understand the change that took place in cinema place after 1989. Film-makers, who sought to establish a relationship with a wider audience, found it embodied in the more or less convoluted political critique of the contemporary situation. The creation of one's own language almost universally meant a establishing a unique 'Aesopean language' that was used to pass content prone to censorship. These secret codes provided an alibi for the creators before the authorities, but were infallibly deciphered by the public. They were deeply rooted in the historical context and were formulated differently in 'the Thaw' of 1956 than in, say, the era of Solidarity. A gradation of the dissident messages' coding could be displayed on a graph: from the still social realist films by Munk and Wajda (Czlowiek na torze - Man on the Tracks; Pokolenie - A Generation), where one could sense a gust of the new times, to the films from the early 80s that directly deny the political foundations of the Polish People's Republic, such as Czlowiek z zelaza (Man of Iron), or Przesluchanie (Interrogation) by Ryszard Bugajski.   The political dimension of this cinema is visible in the concurrence of the rhythm of historical turning points with the generational divisions among the artists - instead of the term 'the Polish Film School', one could say 'cinema of the Polish October' and everyone would understand. Later, there was the 'cinema of slight stabilization' of the sixties and - after the events of March, 1968 - 'cinema of moral unrest' that was to transform later on into 'Solidarity cinema' and 'martial law cinema'. All these terms associate certain aesthetics of communication with a certain fragment of the PPR's political history, to which it was an artistic reaction. It is not accidental that this political language of description has not yet been overcome, for it actually relates to the logic of the Polish cinema's development and to resign from it would be an artificial, fictional treatment that would falsify the picture of the events. The second element that constitutes the Polish specificity was the unusually strong position of the ambitious, artistic cinema that sought new forms of expression in the cinematic language - ones forms that would allow, on par with literature, to touch the most important existential and philosophical issues. This attitude was displayed not only by the film-makers who, like Jerzy Wojciech Has or Grzegorz Królikiewicz, according to the best art circles' patterns shown showed their désinteressement for the wider public and made films for their own sake according to the best art circles' patterns, but also those, who treated the cinema as a tool for social communication. For Andrzej Wajda, Andrzej Munk, Kazimierz Kutz, Roman Polanski, Tadeusz Konwicki or Jerzy Skolimowski, the point of reference was not the popular Hollywood cinema, but European 'auteur' cinema - Italian neorealism, French New Wave or the British Angry Young Men. It is noteworthy that even the lighter films, such as comedies of manners, crime dramas etc. were judged according to the criteria adopted from artistic cinema. This is what happened to the interesting output of Stanislaw Bareja, creator of a series of comedies in the 70s that are still very popular today and have attained a cult status. He was fiercely attacked for his conventional, bourgeois taste and was deemed talent-less, even though he started in the category of entertainment, a different one than those explored by Krzysztof Kieslowski or Krzysztof Zanussi. Of course, apolitical entertainmenting cinema was made in Poland as well, just like the politically correct kind. But it passed into oblivion, without having stirred any emotions. Film-makers that subordinated themselves to the propaganda slogans were not numerous and belonged to the margin. There were no strong personalities or greater talents among them. Certainly, the work of Sylwester Checinski was a certain phenomenon. He was the creator of immensely popular and, at the same time, politically safe comedies. Others, such as Jan Lomnicki or Jerzy Gruza, were responsible for a number of TV series. The first film-maker that wanted to make, as a rule, only good, pure entertainment in the western manner and had the divine spark within himself was Juliusz Machulski, who debuted at the beginning of the 80s. But even in his lighter comedies people saw a subtle stylistic dialogue with the convention of gangster movies (Vabank - Hit the Bank), or political allusions (Seksmisja - Sexmission). The tone of the Polish cinema was imparted by artists and, for that matter, politically engaged artists.  II. 1989 II. 1989This situation changed drastically after the turn of 1989. The change of the political system into democracy caused the cinema to lose its status of a public forum, an unofficial substitute for a free idea exchange. Politics has moved out of the movie clubs and art houses into the parliament. Artists, just like priests, ceased to be the 'speakers for the nation' and, therefore, lost the unique sense of their position and public mission. Many of them have simply turned to politics and were elected to the Parliament. Despite the individual implications of this change, it had a tremendous impact on the language of the cinema. It lost its 'ciphered political code' that smuggled in the message, integrating the people who visited cinemas in order to eat of this 'forbidden fruit'. From 1989 it was possible to say everything in the movies directly, without convoluted allusions. But it was not necessary to go to the cinema to hear it. It was sufficient to turn on the TV and watch the parliamentary proceedings. The new situation influenced the mental state of the 'pure artists' as well. They felt that they had lost the justification for their solemn attitude, since escapism in the times of censorship was something different than what it is in the times of freedom of speech and image. On the other hand, the change of the economic system to capitalism has brought about a new hegemony - the mass consumer. The film-makers, out of fear that the audience will would turn away from them and feeling on their necks the breath of competitive Hollywood films that flooded the Polish cinemas, began to seek a new formula that could replace the old, political thread of communicating with the audience. For the sophisticated artists, on the other hand, capitalism meant difficulties in finding money for their ambitious experiments. The atmosphere of the 'the wide audience always being right' did not allow for such an elevated attitude, especially because the financial means were still flowing mainly from the state budget, not from the accounts of rich patrons that could finance their fancies. All this amounted to great bewilderment among both the political and artistic film-makers. At that time, a lot of projects were made in an attempt to blend the artistic and commercial ambitions and achieve a compromise between the calculation of audience expectations and original artistic experiments. 'Popular auteur cinema', internally contradictory and, because of that, insincere, full of forced artificial ideas, was a reflection of the organizational and financial situation in which Polish cinematography found itself. The production apparatus and the financing system were fit for original cinema, while the projected audience expectations were 'populist' and 'mass-oriented'. This new situation at the beginning of the 90s was best tackled by the debutants. On the one hand, we have Wladyslaw Pasikowski, the author of Psy (Pigs) and Psy 2 (Pigs 2), the biggest commercial success of the time. As a director, he has consciously decided to fake the American action cinema in a Polish setting. Moreover, he created, through his characters, the biggest male star of the 90s - Boguslaw Linda, who is today known for playing plays ruthless and brutally tough guys. On the other hand, there is Jan Jakub Kolski, who consistently builds rural landscapes fused with the fantastic and magical atmosphere of his films which, despite their artistic sophistication and specifically slow narration, won a big audience, especially the flagship Jancio Wodnik (Johnny Aquarius) that was shown in Cannes, outside the competition. The success of these two artists became a signpost in the mid-90s for many film-makers that were seeking their place within thise new situation. Pasikowski had many imitators, such as Jaroslaw Zamojda or Olaf Lubaszenko, whose aim was to reach the younger audience, fascinated with new phenomena that were known only from American films, such as organized crime, the everyday life of gangsters, the luxury of upstart financial and social elites etc. Next, the work of Kolski has created a fashion for cinema in 'Czech style' that presents, with humour and irony, the lives of 'ordinary people' somewhere in the province, where time seems to flow differently. This fashion is already gone. 'Ordinary people' are shown without sparing any severity, for example in Czesc Tereska (Hi, Tereska) by Robert Glinski, Edi by Piotr Trzaskalski or Zurek (Sour Soup) by Ryszard Brylski. Kolski himself has tested his strength beyond his characteristic style in adaptations of books by Hanna Krall (Daleko od okna - Keep Away from the Window) or Witold Gombrowicz (Pornografia - Pornography). Kolski's newest film Jasminum, although very well received by the public, returns to the old idiom, bordering on auto-parody. Among Kolski's peers, who, despite the temptations of populism, have remained true to their artistic choices from the moment of their debut, there are people like Mariusz Trelinski and Dorota Kedzierzawska. Their sophisticated,, precise, and characteristic films have almost always appealed to the critics, but rarely reached a wider public. III. The BreakthroughTowards the end of the 90s, there was a breakthrough in the Polish cinema.  Still from the movie, photo: Mirek Noworyta / Agencja SE / East News Still from the movie, photo: Mirek Noworyta / Agencja SE / East NewsTwo great productions based on classics of Polish literature - Ogniem i mieczem (With Fire and Sword, 1999) by Jerzy Hoffman, based on a novel by Henryk Sienkiewicz, and Pan Tadeusz (Pan Tadeusz: The Last Foray in Lithuania ,1999) by Andrzej Wajda, based on the national epic by Adam Mickiewicz, were a bigger box-office success than all the American films shown at that time combined. For the first time since 1989, the Polish cinema has proven that it has its public. This success of film-makers of the older generation has encouraged others, and soon other adaptations followed with record budgets (e.g. Quo Vadis by Jerzy Kawalerowicz, ca $22 million) and advertising campaigns hitherto unseen in Poland. Most of them brought profits. At the same time, there appeared such movies as Dlug (The Debt, 1999) by Krzysztof Krauze and Czesc Tereska (Hi, Teresksa, 2000) by Robert Glinski, which rebuilt the dialogue between the film-makers and the audience that was broken at the beginning of the 90s. In both of these films, the directors speak in the convention of a public confession and the public felt that they are not only a ‘target group', but also a partner in a discussion on the problems that affect everyone who lives 'here'. In their look at the danger of crime and poverty of the big city high-rise complex, the directors have assumed the perspective of public opinion. They observe that the gangster who demands protection money is not a photogenic and manly 'black character', but a real threat, while the groups of 'stray' children rummaging through the vast neighbourhoods are not an abstract phenomenon from sociological papers, but an acute reality. The newest film by Krzysztof Krauze, Plac Zbawiciela (Saviour Square), winner at the 2006 Polish Feature Film Festival in Gdynia, is a continuation of this form of dialogue, in which the viewer is treated as a partner and not as a consumer of sensation. In Krauze's deep, psychological description of a family conflict, which is the main subject of the story, there are no easy, media-like divisions into the guilty and the victim. The tragedy that takes place at the end of the film is pictured as a result of a 'normal' situation from an 'average' home, which in turn becomes a signal from the author that the problem touches us all, including the makers of the film. Towards the end of the 90s, there emerged a strong group of young people who received their film education already in the new reality. Some of them, like Malgorzata Szumowska, Lukasz Barczyk, Iwona Siekierzynska, Artur Urbanski, Marek Lechki or Dariusz Gajewski were given a chance to debut in the public television (TVP) as part of a cycle 'Generation 2000'. This rather misleading name - the age range of these young artists is rather large - accurately renders the intention of the producer: to select new individuals, whose artistic sensibility and knowledge of the world have been shaped throughout the 90s. Others, like Piotr Trzaskalski, Andrzej Jakimowski or Przemyslaw Wojcieszek have made it to the top themselves by finding private producers for their projects or by beginning from the semi-professional stance of 'off-cinema'. Of course, their films are extremely varied. But there is a common need for communication that links them. They want to tell the viewer (sometimes gaudily, sometimes in a gibberish manner, sometimes in plain prose) of their own certainty or uncertainty, or, to speak loftily, their truth. But before it takes place, they show the viewer how this truth has been constituted, where it came comes from and from which point of view it can be seen. In this way I see Patrze na ciebie Marysiu (I'm Looking at You, Mary) and Przemiany (Changes) by Lukasz Barczyk, Edi by Piotr Trzaskalski, Glosniej od bomb (Louder Than Bombs) by Przemyslaw Wojcieszek and Moje miasto (My Town) by Marek Lechki. The first shouts at me "I will saytell what I am afraid of", the second mutters "I will say what I believe in", the third announces "I will say what is going on here" etc. There is none of the fake seriousness, so often encountered among young actors, no tension, insolent play or the usual commercial calculation. These films are rather a humble confession, an attempt at a definition of one's own place, sometimes a therapeutic session, a notebook of everyday matters, or a ceremony of intimate emotions. Despite the display of a private perspective, I would not call this type of cinema egotistic or self-centred. The intimate mood is rather a reaction to the overwhelming ideological buzz of the media and the politicized history of Polish cinema. Paradoxically, thanks to the restriction of the field of view to a private perspective, there is a lot of surrounding reality in the films of the younger generation in comparison with their older colleagues. A sharp, satiric vision of small-town boredom kindled with the capitalistic rouse of the 'new money' is drawn in Glosniej od bomb (Louder Than Bombs) by Przemyslaw Wojcieszek. His film has been brilliantly supplemented a few years later with Wesele (The Wedding) by Wojciech Smarzowski, a movie that through its uncompromising spitefulness in the portrayal of modern Polish countryside balances on the border of an anarchistic lampoon. Two students' struggle with life is passionately and humorously described by Iwona Siekierzynska. In the tripartite Oda do radosci (Ode To Joy), well received by the critics, the three debuting directors, Anna Kazejak-Dawid, Jan Komasa and Maciej Migas, touch upon a key experience of their peers' generation - the immense wave of emigration in search for money among young Poles, who are discouraged by unemployment and the ruthless battle for survival at the end of the 90s in Poland. Dariusz Gajewski, on the other hand, winner of the 2003 Polish Feature Film Festival in Gdynia, has contained in his Warszawa (Warsaw) something that has been long awaited by everyone - a visual metaphor of the modern times. It is neither, as Natalia Koryncka would have it in Amok, the stock exchange building, nor a big city high-rise, a ruined state farm or the police headquarters, as others have conceived of it. I do not know of a place that would describe our times better than our capital city, with its Communist Party Headquarters changed into a business centre and the Ministry of National Education situated in the former Gestapo seat. The makers of Warszawa have tried to capture this fundamental confusion of the reality in which the Poles now live. This permanent fit of group amnesia and the common dressing-up function as a panic escape from our own identity;, too painful, poor and traumatized to bear, be ill with and finally cure. For the first time in ages, Warsaw does not pretend to be the backdrop for a film about the rich, the hooligan jocks or the Europeans, but precisely Warsaw, a place that speaks for itself. And this is the real triumph of cinema over reality. Author: Mateusz WernerFrom the catalogue "Young Polish Cinema" published by the Adam Mickiewicz Institute, June 2007 |

|

|

|

Post by pieter on Aug 13, 2014 4:04:23 GMT -7

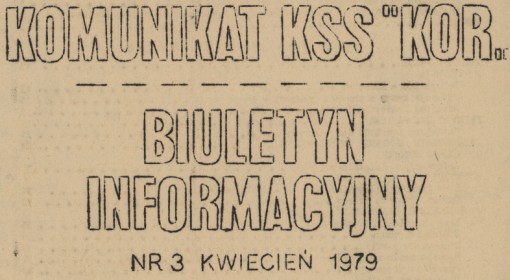

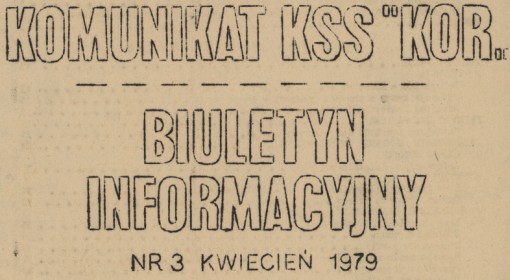

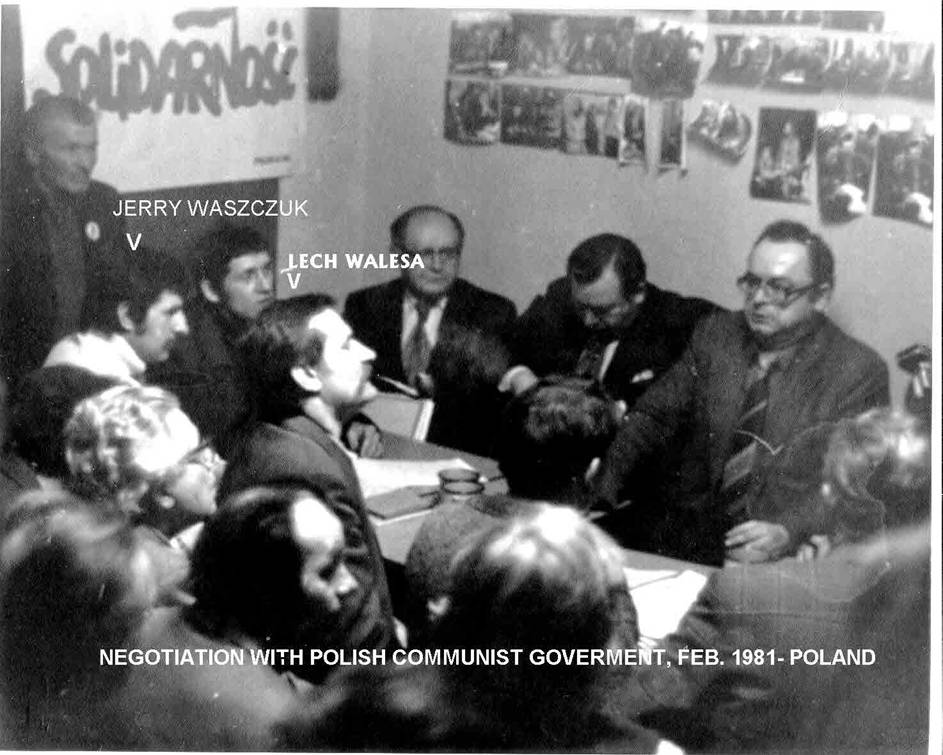

The Workers' Defense Committee (Polish: Komitet Obrony Robotników pronounced, KOR)  Opis: Wrzesieñ 1980, Warszawa. Dzia³acze Komitetu Obrony Robotników - Adam Michnik i Jacek Kuroñ - portret. Fot. Tomasz Michalak [opozycja, KOR]The Workers' Defense Committee Opis: Wrzesieñ 1980, Warszawa. Dzia³acze Komitetu Obrony Robotników - Adam Michnik i Jacek Kuroñ - portret. Fot. Tomasz Michalak [opozycja, KOR]The Workers' Defense Committee (Polish: Komitet Obrony Robotników pronounced, KOR) was a Polish civil society group that emerged under communist rule to give aid to prisoners and their families after the June 1976 protests and government crackdown. KOR was an example of successful social organizing based on specific issues relevant to the public's daily lives. It was a precursor and inspiration for efforts of the Solidarność trade union a few years later.  24-30.05.1977, Warszawa, Polska. Głodówka członków i współpracowników KOR (Komitet Obrony Robotników) w kościele Św. Marcina w Warszawie, w proteście przeciwko przetrzymywaniu w areszcie 5 robotników z Radomia i Ursusa oraz członków i sympatyków KOR. Na zdjęciu uczestnicy głodówki, od lewej w dolnym rzędzie: Jerzy Geresz, Henryk Wujec, o. Aleksander Hauke-Ligowski, Tadeusz Mazowiecki (rzecznik głodujących), Lucyna Chomicka, Stanisław Barańczak; w górnym rzędzie: Ozjasz Szechter, Joanna Szczęsna, Bogusława Blajfer, Zenon Pałka, Eugeniusz Kloc, Kazimierz Świtoń, Barbara Toruńczyk, Bohdan Cywiński, Danuta Chomicka. Fot. NN, zbiory Ośrodka KARTA (z archiwum Eugeniusza Kloca, przekazał Jan Strękowski)History 24-30.05.1977, Warszawa, Polska. Głodówka członków i współpracowników KOR (Komitet Obrony Robotników) w kościele Św. Marcina w Warszawie, w proteście przeciwko przetrzymywaniu w areszcie 5 robotników z Radomia i Ursusa oraz członków i sympatyków KOR. Na zdjęciu uczestnicy głodówki, od lewej w dolnym rzędzie: Jerzy Geresz, Henryk Wujec, o. Aleksander Hauke-Ligowski, Tadeusz Mazowiecki (rzecznik głodujących), Lucyna Chomicka, Stanisław Barańczak; w górnym rzędzie: Ozjasz Szechter, Joanna Szczęsna, Bogusława Blajfer, Zenon Pałka, Eugeniusz Kloc, Kazimierz Świtoń, Barbara Toruńczyk, Bohdan Cywiński, Danuta Chomicka. Fot. NN, zbiory Ośrodka KARTA (z archiwum Eugeniusza Kloca, przekazał Jan Strękowski)History This organization was the first major anti-communist civic group in Poland, as well as Central- and Eastern Europe. It was born of the outrage at the government's crackdown in June 1976. Its stated purpose was to create " new centers of autonomous activity." It raised money through sales of its underground publications, through fund-raising groups in Paris and London, and grants from Western institutions. KOR sent open letters of protest to the communist government and organized legal and financial support for the families of political detainees. The leaders of the organization established an activities and coordination center and offered analysis on workers’ conditions within Poland. They often collaborated with Western journalists on writing and publishing articles. The group worked with sympathetic lawyers to get better representation for striking workers and obtained medical diagnoses from doctors which they presented as evidence of police brutality in court trials. The group smuggled in mimeograph machines to print its underground newsletter, Komunikat, which had a circulation of around 20,000 by 1978.  As a side project of KOR, an underground publishing house called NOWA was founded using mimeograph machines owned by KOR. It printed material critical of the regime and reproduce banned writings from thinkers outside of the Warsaw Pact, such as George Orwell. NOWA had its own print shops, storehouses, and distribution network, and financed itself through sales and contributions. In the fall of 1977 KOR collaborated with intellectuals in the Warsaw community to establish the Flying University, a series of lectures organized by unofficial student groups to discuss ideas about freedom that could not be debated in public. The government harassed KOR members as it did any other civil society in Poland: beating up and jailing dissidents, infiltrating and interrupting lectures, and conducting searches of dissidents’ houses.  However, KOR became an inspiration for the nation when its efforts finally paid off when the Polish government declared amnesty for jailed strikers in the spring of 1977. In that year, it was renamed to Committee for Social Self-defence KOR ( Komitet Samoobrony Społecznej KOR). KOR published an underground paper, Robotnik (" The Worker"—the same title as Józef Piłsudski's underground paper)  Legacy LegacyThe organization is often forgotten in the wake of Solidarność success in the 1980s, but KOR remained an important force in bringing down communism in Poland.  polska.newsweek.pl/pogrzeb-romaszewskiego-sylwetka-zbigniewa-romaszewskiego-newsweek polska.newsweek.pl/pogrzeb-romaszewskiego-sylwetka-zbigniewa-romaszewskiego-newsweek,artykuly,280839,1.html niezalezna.pl/16519-jutro-35-rocznica-powstania-kor

|

|

|

|

Post by pieter on Aug 13, 2014 16:03:50 GMT -7

Polish pop groups and musicians of the seventies and eighties Polish Pop groep from Krakow from the seventies and eightiesserpent.pl/pathman/atman.htmlsavagesaints.blogspot.nl/2008/01/atman-tradition-1999.htmlBasia Trzetrzelewska with Matt Bianco Poland Polish Pop groep from Krakow from the seventies and eightiesserpent.pl/pathman/atman.htmlsavagesaints.blogspot.nl/2008/01/atman-tradition-1999.htmlBasia Trzetrzelewska with Matt Bianco Poland was known for it's excellent Jazz in the Polish Peoples Republic and the rest of the world. Especially Kraków with it's Jazz music basement pubs was a centre of Polish jazz. I went to one of these excellent Jazz basement clubs in Krakow in April 2004, and enjoyed an evening of very good, professional top jazz. I was glad that my Dutch and German companions could enjoy this music and experience Poland, Polish culture, Polish music, Polish people, Polish hospitality and Modern Poland. They got a very good impression of Kraków and Poland. They liked the Polish people, the city, the Polish food, Polish art and the history and heritage of the Polish people. They considered Kraków a romantic, exciting, multi-layered and cosmopolitan city with it's old Polish core, and Italian Renaissance, Austrian Habsburg and Jewish elements (Kazimierz). They were surprised about the Underground (alternative/Indie) subculture of students, squaters, artists, musicians, intellectuals and others they saw there. We went out in an old fashionate ' New Wave' (or today Gothic kind of) pub-discotheque-nightclub in which they played The Cure, New Order, Siouxie and the Banshees and some Polish pop music. The atmosphere was very nice and cosy. It was nice to visit the Krakow art academy and talk with teachers and students there. We like the Museum 'Bunkier' and other art museums, like the museum with the painting of Leonardo DaVinci. They played these songs in that Polish club in Krakow: (I liked the fact that it was so Underground that foreign tourists couldn't find it. A Dutch Pole had found it for us via his Polish connections. He also took us to an original Polish restaurant with Polish cuisine. He was a student of the art academy in Arnhem. Both of his parents were Polish. He spoke both excellent Dutch and Polish.) It was fun and great to see real Slavic Polish excentric New Goth girls in the Cure and Siouxsie Sioux style. They were more theatrical and baroc than their Western counterparts.   Something like this Polish girl Something like this Polish girl And this one And this oneI was stil in my own black clothes period (ninetees and early 21th century) period (black t-shirts, black jeans, black shoes and black socks). So I fitted in the Polish Undergroud scene of that club. Young women and men and some older Polish guys who were attracted to the alternative lifestyle and music of these youngsters. There was a lively New Wave Gothic and Punk scene there. I also saw a few Skinheads in Kraków, but not many. The city breathed a tolerant, open and sophisticated atmosphere. I remember that I read that 126,000 of the 800,000 people living in Kraków were university students of the Jagiellonian University. (Polish: Uniwersytet Jagielloński) My Dutch and German friends considered Kraków to be a romantic city with an interesting past, present (back then in 2004) and a city with a bright future, due to the mix of old and new elements in the city. Personally I also liked the churches, Wawel, the Wisla river, the old boulevard and the Old Market square. It were 5 intense days back then. We walked a lot and used the tram, busses and taxi's. Cheers, Pieter

|

|

|

|

Post by Eric on Aug 13, 2014 17:18:14 GMT -7

Where's Maryla Rodowicz? She had some great songs.

|

|

|

|

Post by Jaga on Aug 13, 2014 21:13:46 GMT -7

Pieter,

Basia was still quite popular in the US when I came here in 90s. Poland is know for its soft jazz. I like her songs, but she disappeared....

|

|

|

|

Post by pieter on Aug 14, 2014 10:21:50 GMT -7

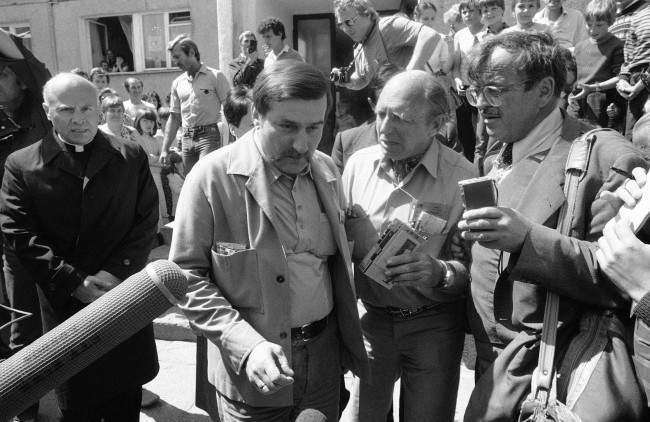

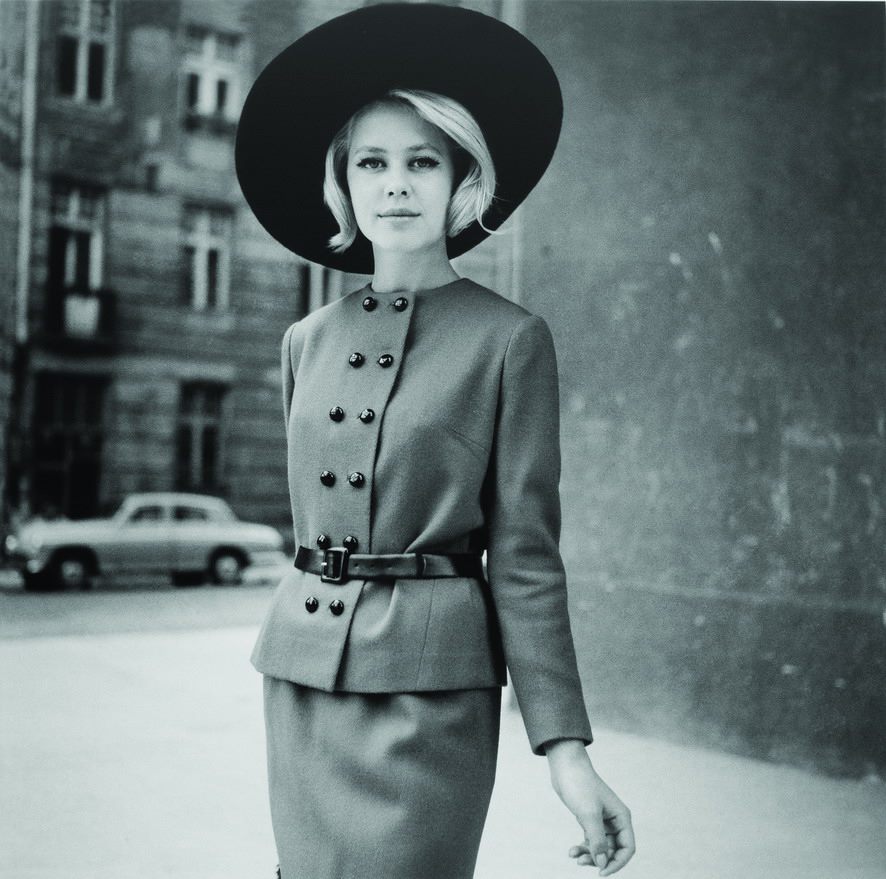

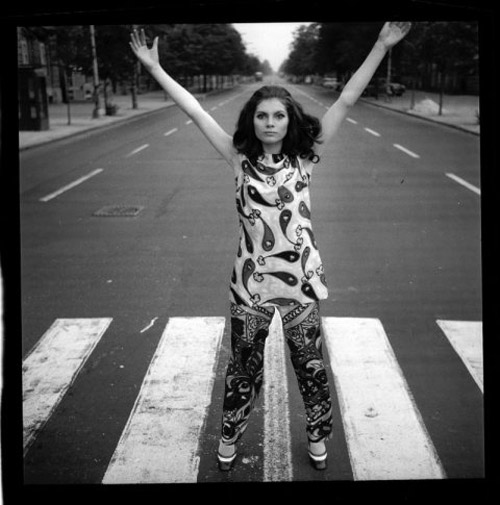

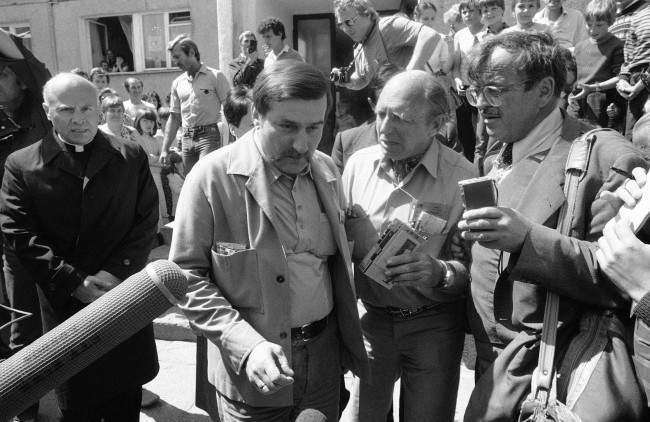

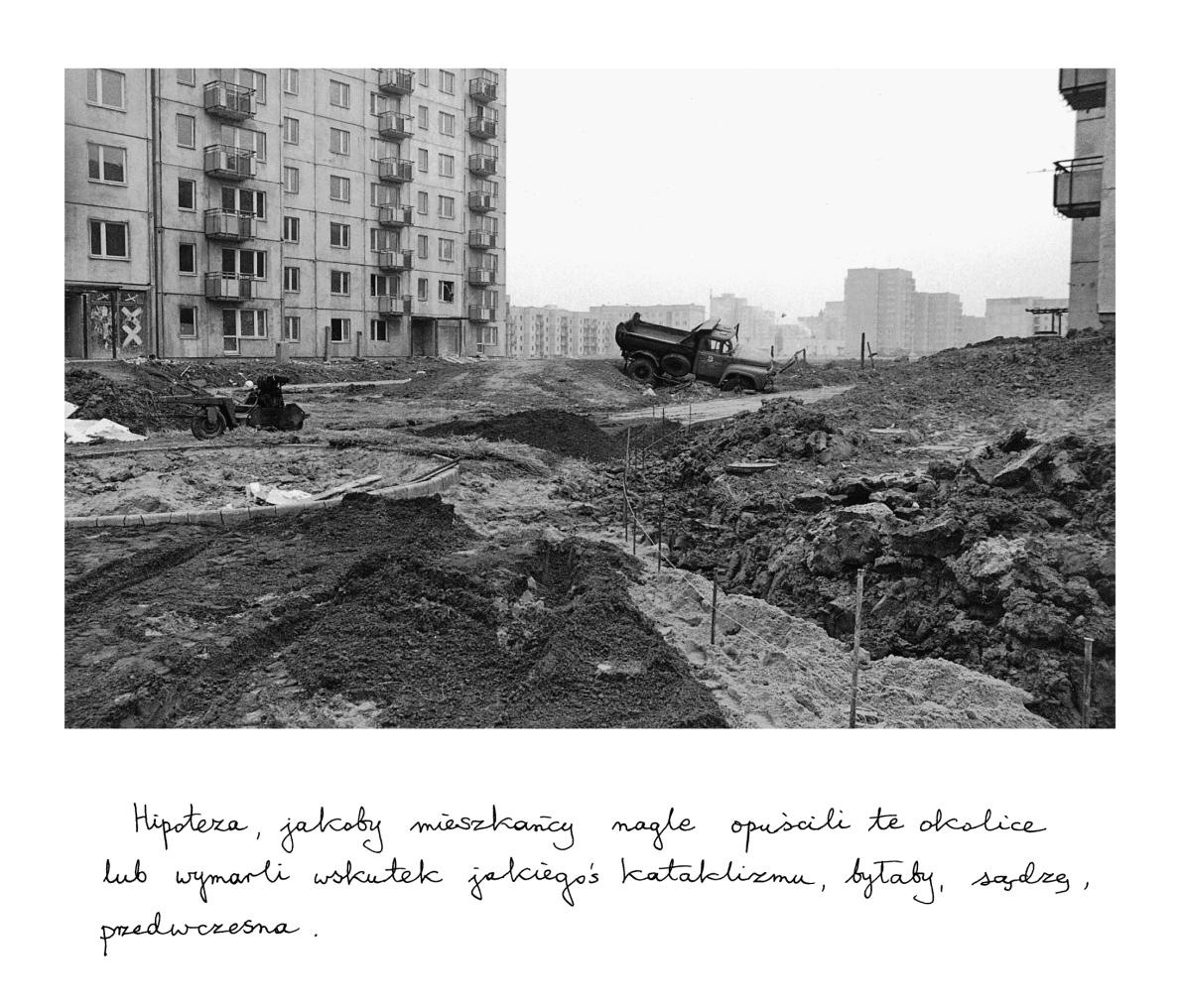

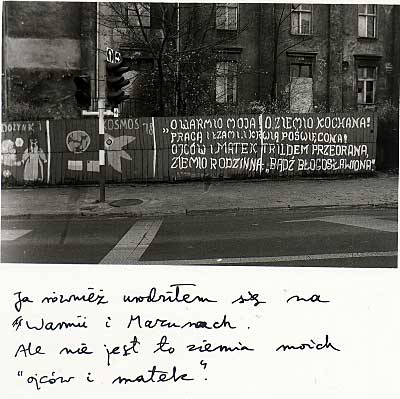

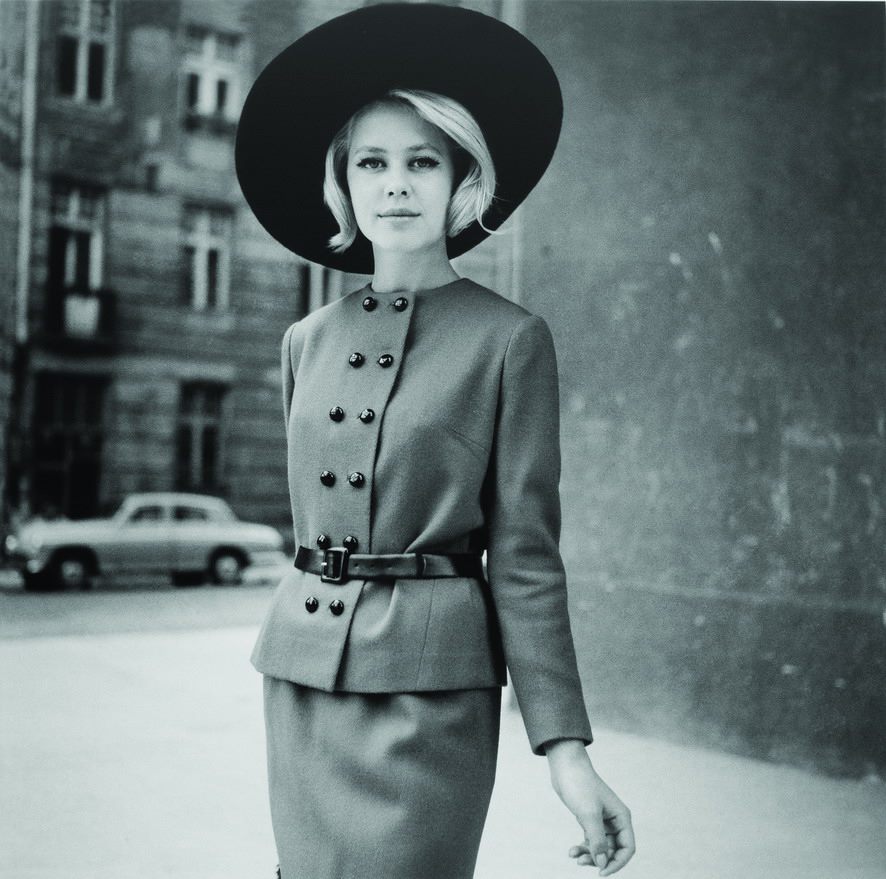

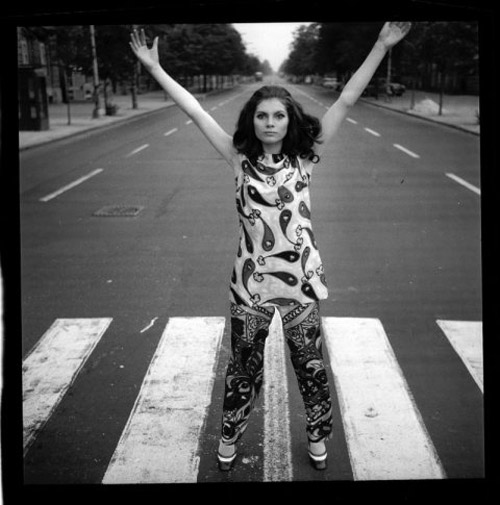

I found even more images of communist Poland. It is amazing how much material you can find on the Internet.     Warsaw, 1980, before the days of AAA, Maluch's tiny frame could hold its own on Polish roads and in case of an accident offered the drivers a lightweight towing option, photo: Jerzy Michalski / Forum Warsaw, 1980, before the days of AAA, Maluch's tiny frame could hold its own on Polish roads and in case of an accident offered the drivers a lightweight towing option, photo: Jerzy Michalski / Forum Władysław Gomułka and Nicolae Ceaușescu Władysław Gomułka and Nicolae Ceaușescu  The late 1960′s were characterized by radical political change, by counterculture and social revolution. In Poland, the Communist Regime worked hard to suppress and censor information as well as create propaganda to twist reality. However nothing could effectively shut out the energy of the generation and in 1968, something finally had to give. The late 1960′s were characterized by radical political change, by counterculture and social revolution. In Poland, the Communist Regime worked hard to suppress and censor information as well as create propaganda to twist reality. However nothing could effectively shut out the energy of the generation and in 1968, something finally had to give. Autumn 1981. Henchmen of the Communist Party get ready... Autumn 1981. Henchmen of the Communist Party get ready... After World War Two Poland ended its contract with Fiat. During the communist era the state owned car firm FSM made the Syrena car After World War Two Poland ended its contract with Fiat. During the communist era the state owned car firm FSM made the Syrena car The Saragossa Manuscript (Wojciech Has, 1965) The Saragossa Manuscript (Wojciech Has, 1965) Z uk van in Nowa Huta (Kraków, Poland)  Solidarity leader Lech Walesa issued a statement after the murder of the Roman-Catholic priest Jerzy Popieluszko by the Polish secret service Security Służba Bezpieczeństwa, saying: “The worst has happened. Someone wanted to kill and he killed not only a man, not a Pole, not only a priest. Someone wanted to kill the hope that it is possible to avoid violence in Polish political life.” Solidarity leader Lech Walesa issued a statement after the murder of the Roman-Catholic priest Jerzy Popieluszko by the Polish secret service Security Służba Bezpieczeństwa, saying: “The worst has happened. Someone wanted to kill and he killed not only a man, not a Pole, not only a priest. Someone wanted to kill the hope that it is possible to avoid violence in Polish political life.”   A sculpture in Wroclaw, Poland designed by Jerzy Kalin to commemorate victims of the Communist regime. A sculpture in Wroclaw, Poland designed by Jerzy Kalin to commemorate victims of the Communist regime.  Solidarność member Dr. Zbigniew Romaszewski during his trial in 1983. He was sentenced to prison for “broadcasting false information.” Solidarność member Dr. Zbigniew Romaszewski during his trial in 1983. He was sentenced to prison for “broadcasting false information.” Politics and Fashion in a Communist Poland Politics and Fashion in a Communist Poland Politics and Fashion in a Communist Poland Politics and Fashion in a Communist Poland Tadeusz Mazowiecki somewhere during the eighties Tadeusz Mazowiecki somewhere during the eighties May 1st, under communist rule they celebrated as Labour Day with government-endorsed parades, concerts and similar events. Following the 1989 changes, they decided to keep this day a public holiday but to give it the neutral name of State Holiday. May 1st, under communist rule they celebrated as Labour Day with government-endorsed parades, concerts and similar events. Following the 1989 changes, they decided to keep this day a public holiday but to give it the neutral name of State Holiday. Nysa 522 Ambulance - Museum of Fire and Rescue Vehicles, Krakow Poland Nysa 522 Ambulance - Museum of Fire and Rescue Vehicles, Krakow Poland Martial Law, 1981 Martial Law, 1981  Polish Buddhists who followed the Tibetan Buddhism in their communist part of Europe during the seventies Polish Buddhists who followed the Tibetan Buddhism in their communist part of Europe during the seventies The Pope is credited with helping end communist rule in Poland. Here, in June 1987, he hugs Lech Walesa, leader of Poland’ Solidarity trade union and later the country first post-communist president, during the pope’s visit to the northern port of Gdansk. (Photo: MARI/Getty Images) The Pope is credited with helping end communist rule in Poland. Here, in June 1987, he hugs Lech Walesa, leader of Poland’ Solidarity trade union and later the country first post-communist president, during the pope’s visit to the northern port of Gdansk. (Photo: MARI/Getty Images) First Communion Children, Poland 1950s First Communion Children, Poland 1950s  Zomo Units in Poland (special police forces during the Peoples republic, notorious under the Polish population) Zomo Units in Poland (special police forces during the Peoples republic, notorious under the Polish population) In the 1970s Barbara Hoff started designing lovely simple folk-inspired clothes out of natural textiles, but these were awfully hard to get - women stormed the shop and grabbed the whole collection down to the last scarf within an hour or two. (Jaga, you talked about it over here. Barbara Hoff inspired you and other young women back then.) In the 1970s Barbara Hoff started designing lovely simple folk-inspired clothes out of natural textiles, but these were awfully hard to get - women stormed the shop and grabbed the whole collection down to the last scarf within an hour or two. (Jaga, you talked about it over here. Barbara Hoff inspired you and other young women back then.)  Funny thing is, in the 1980s literally everyone rebellious in communist Poland gathered in church. Here, Polish hippies on the pilgrimage to the Black Madonna of Częstochowa Funny thing is, in the 1980s literally everyone rebellious in communist Poland gathered in church. Here, Polish hippies on the pilgrimage to the Black Madonna of Częstochowa The Hippie movement came to the Polish side of the Iron Curtain in the 1970s (Polish Hippies tried to dress on roughly hippie lines even in the 80s), and presented a formidable challenge to the locals dressing capacities. The Hippie movement came to the Polish side of the Iron Curtain in the 1970s (Polish Hippies tried to dress on roughly hippie lines even in the 80s), and presented a formidable challenge to the locals dressing capacities.  Polish Communist Hilary Minc Wearing Hat and Coat (fifties)[/i]  Car traffic in communist Poland Car traffic in communist Poland Workers Of The Gdansk Shipyard, 1980 Workers Of The Gdansk Shipyard, 1980 Jazz Camping Kalatówki, 1959. Pictured: Krzysztof Komeda, Andrzej Trzaskowski, Stanisław "Drążek" Kalwiński. Photo: Wojciech Plewiński / Forum Jazz Camping Kalatówki, 1959. Pictured: Krzysztof Komeda, Andrzej Trzaskowski, Stanisław "Drążek" Kalwiński. Photo: Wojciech Plewiński / Forum Communist Workers apartment blocks, 1979, Warsaw Suburbs, Poland Communist Workers apartment blocks, 1979, Warsaw Suburbs, Poland |

|

|

|

Post by pieter on Aug 14, 2014 11:30:26 GMT -7

|

|

|

|

Post by pieter on Aug 14, 2014 14:42:16 GMT -7

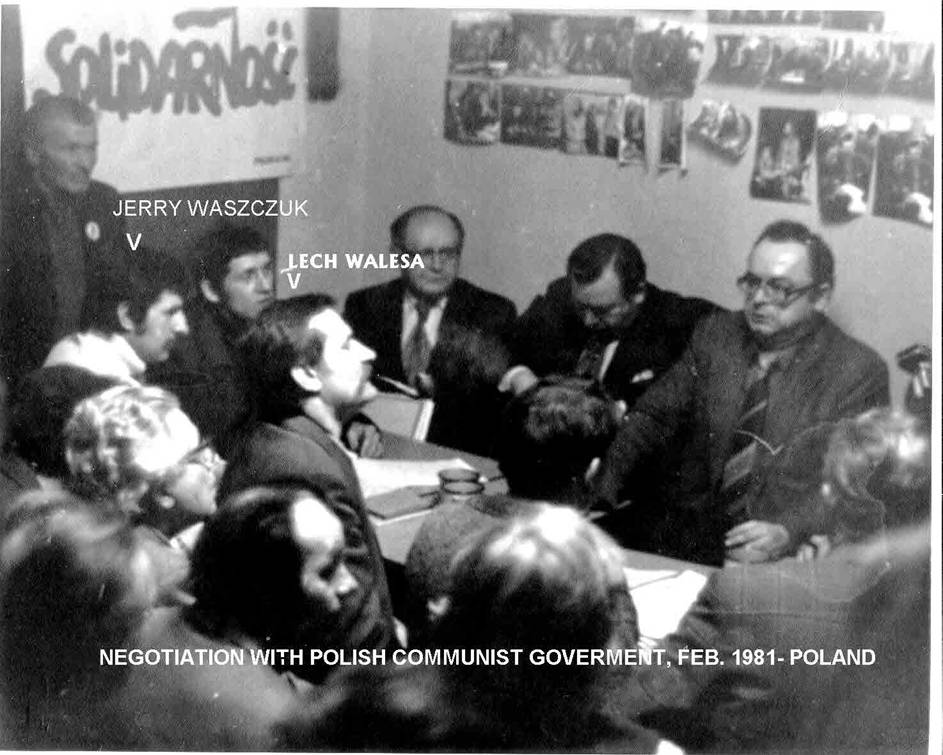

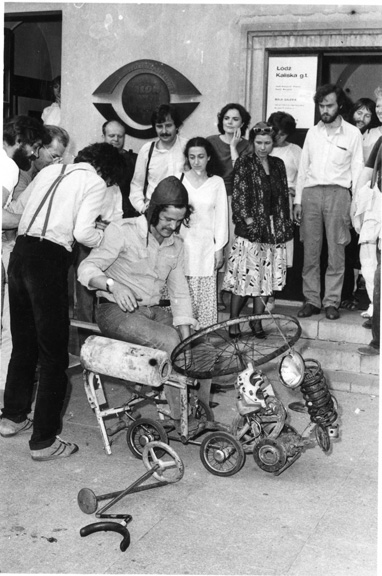

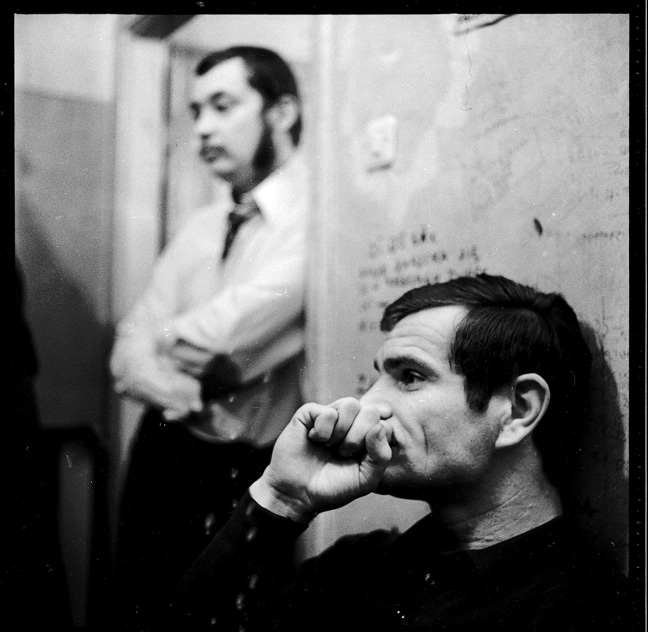

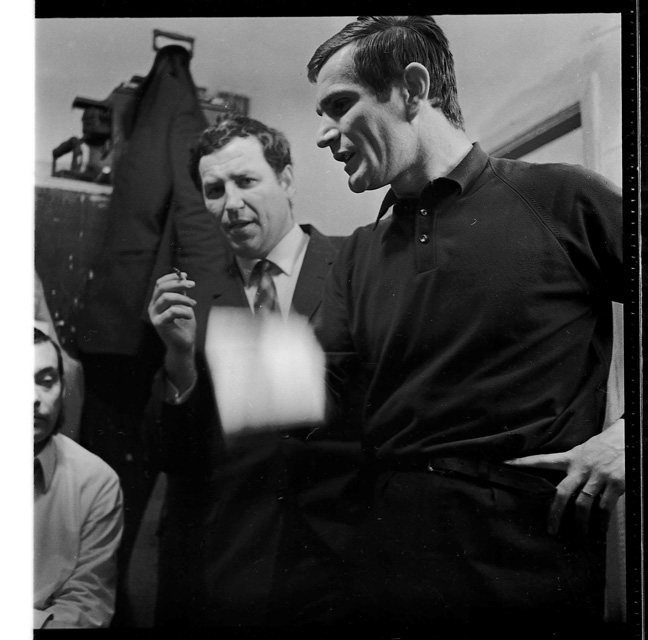

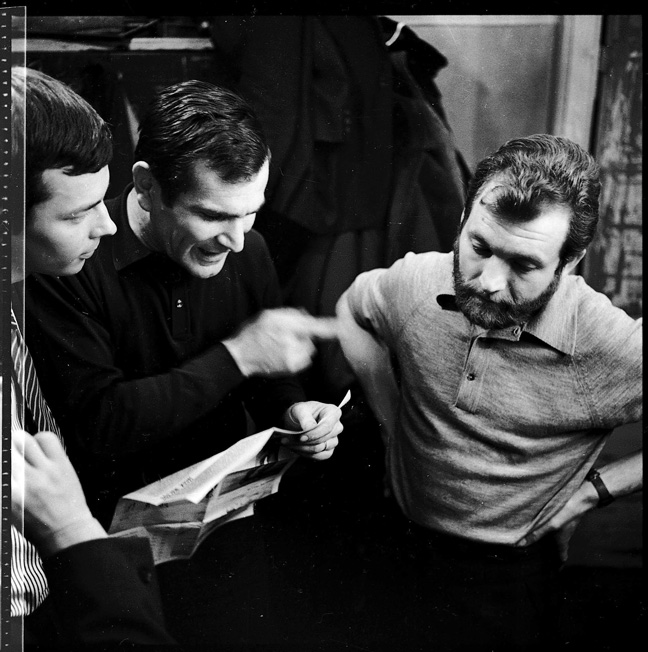

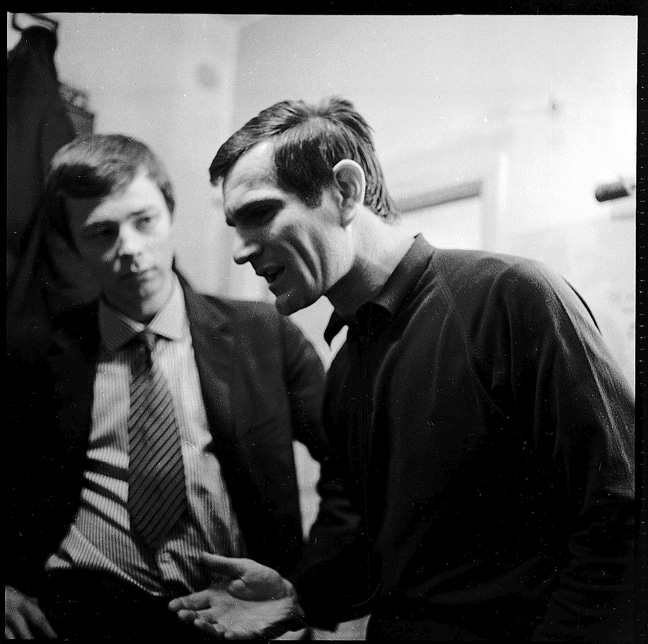

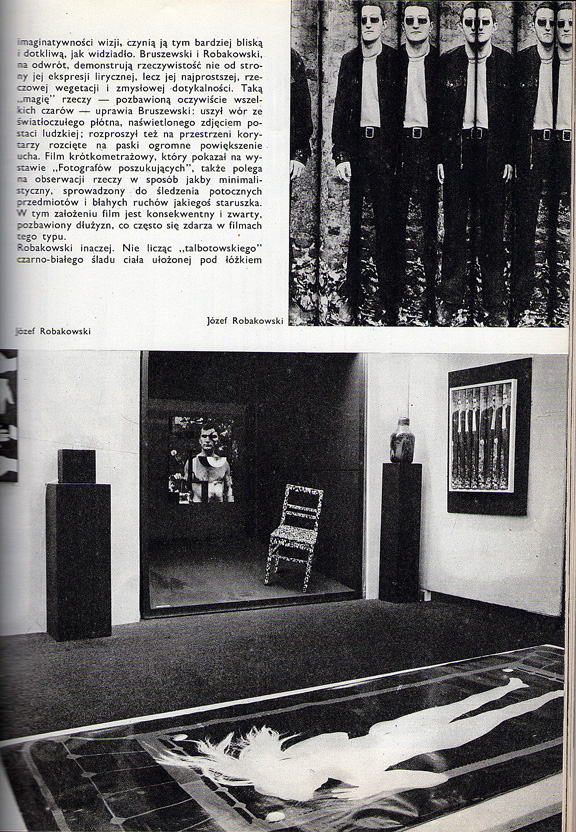

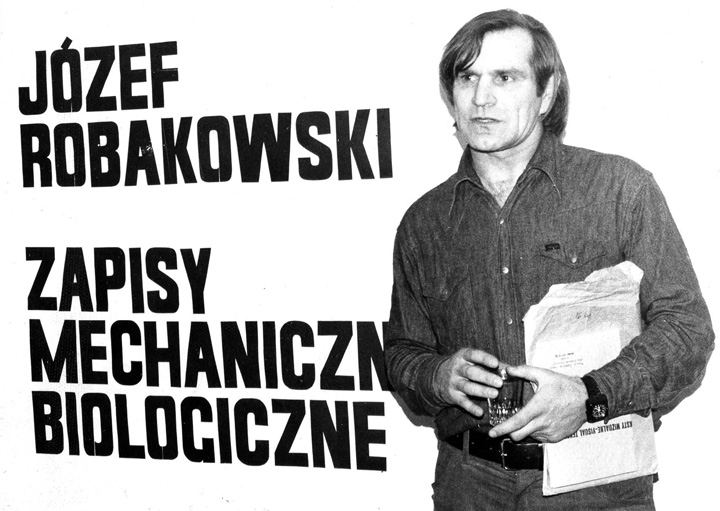

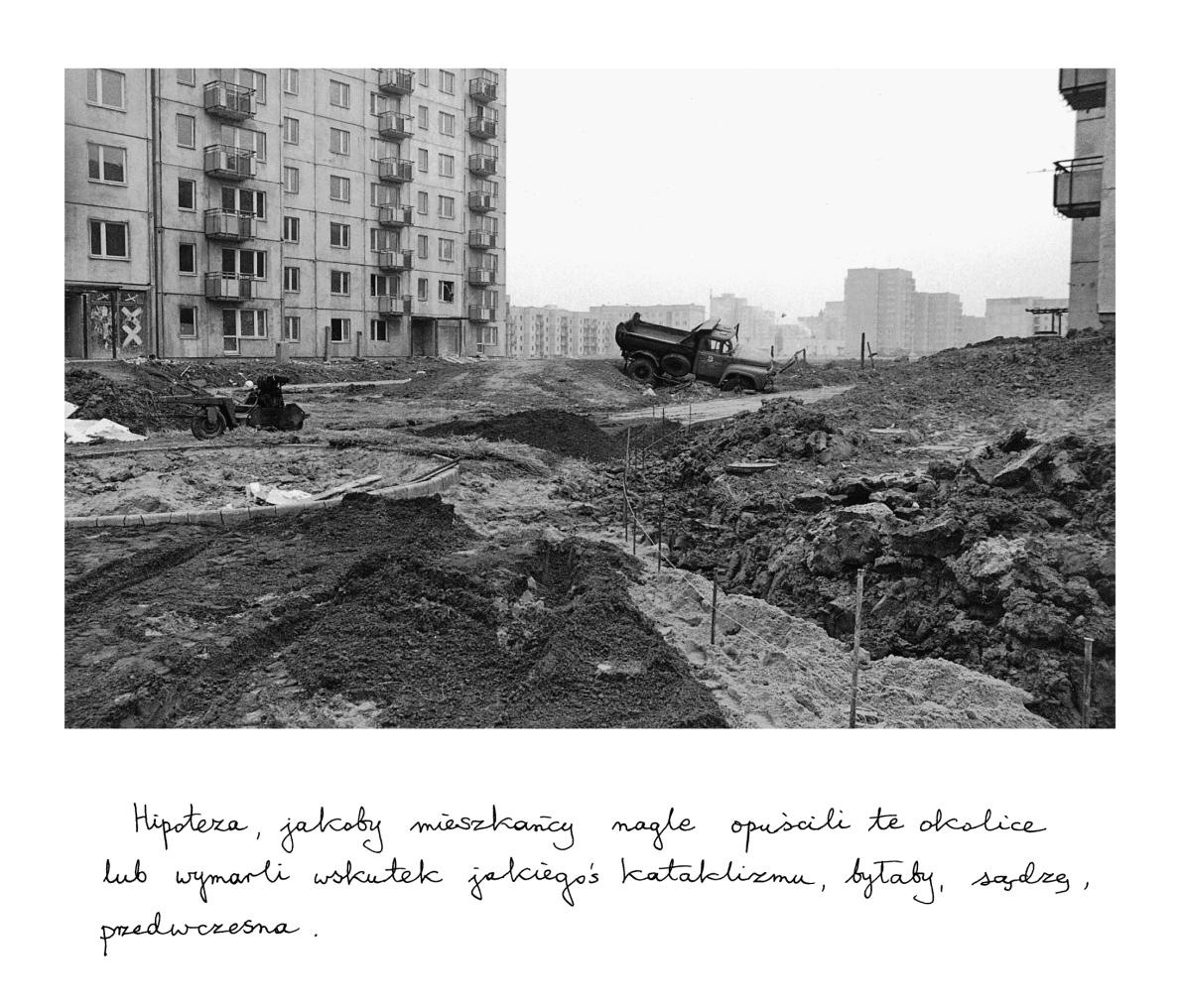

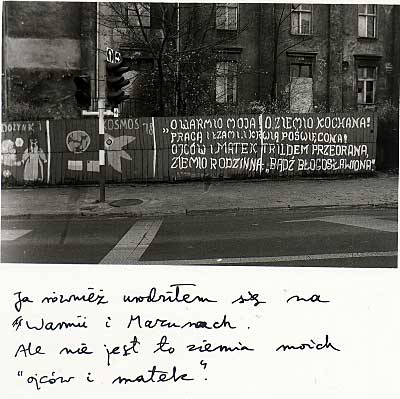

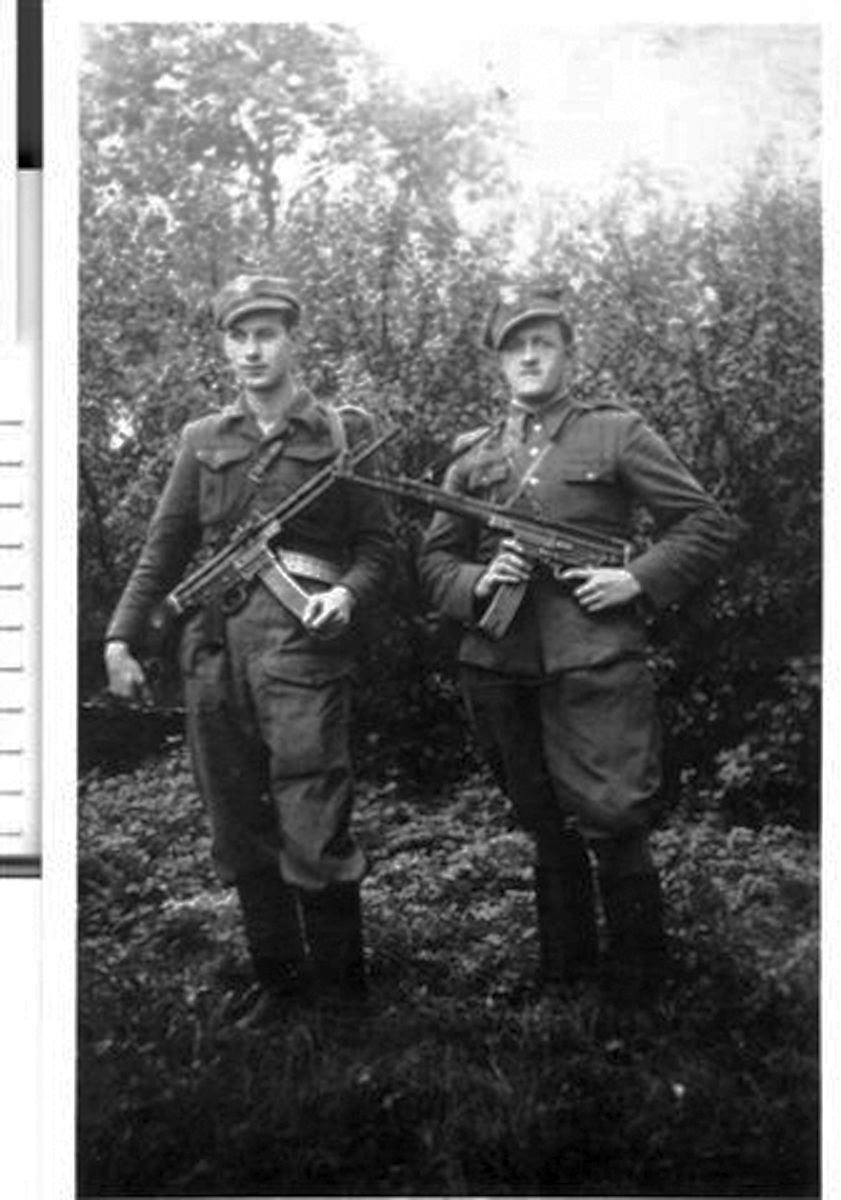

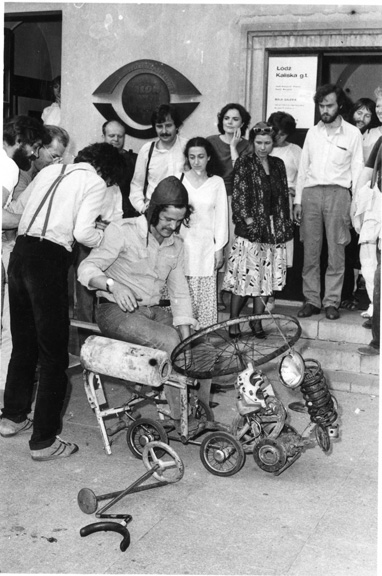

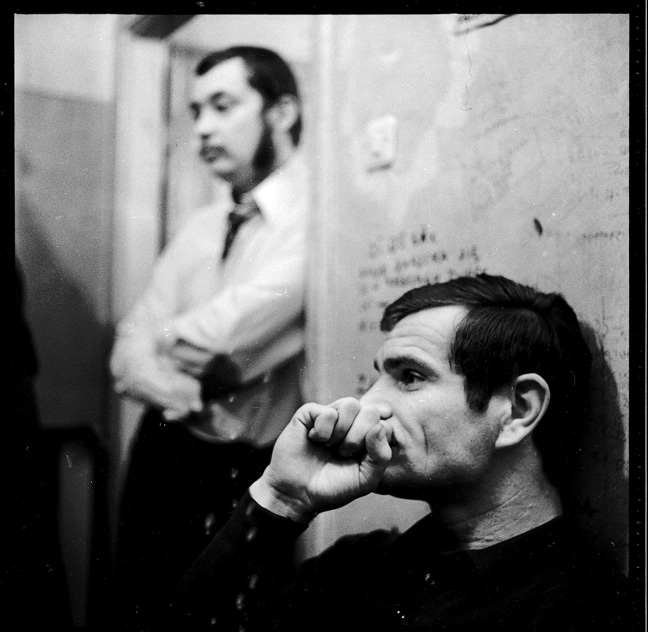

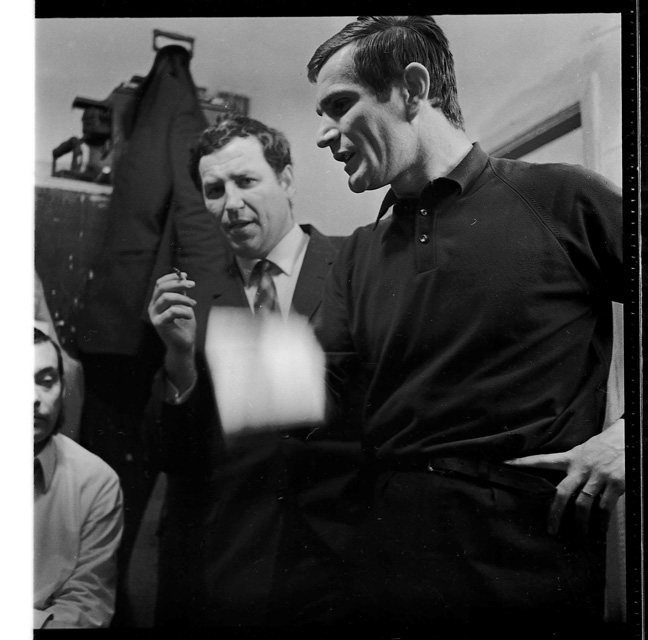

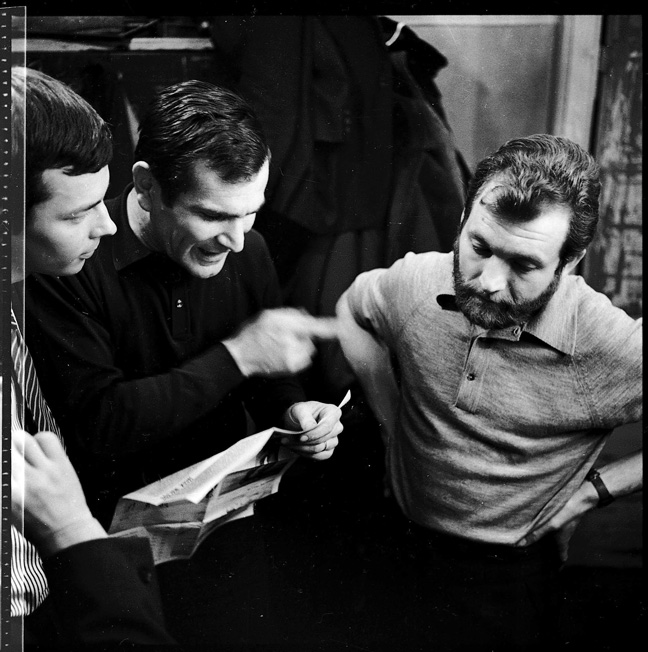

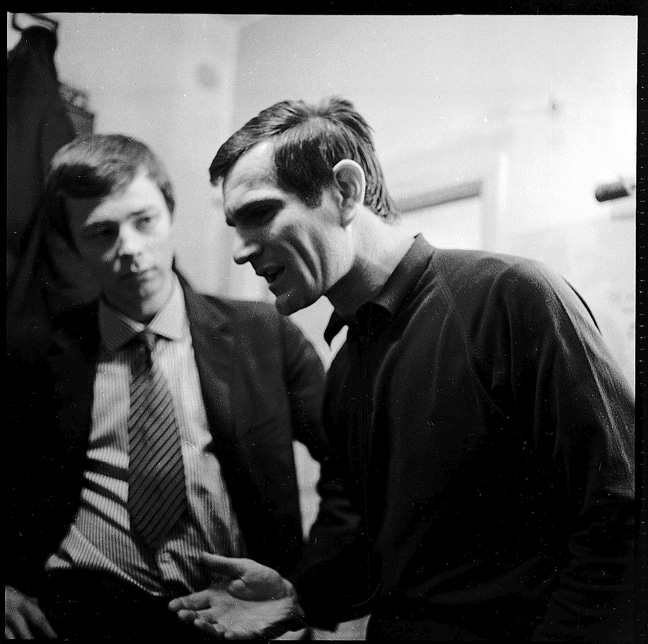

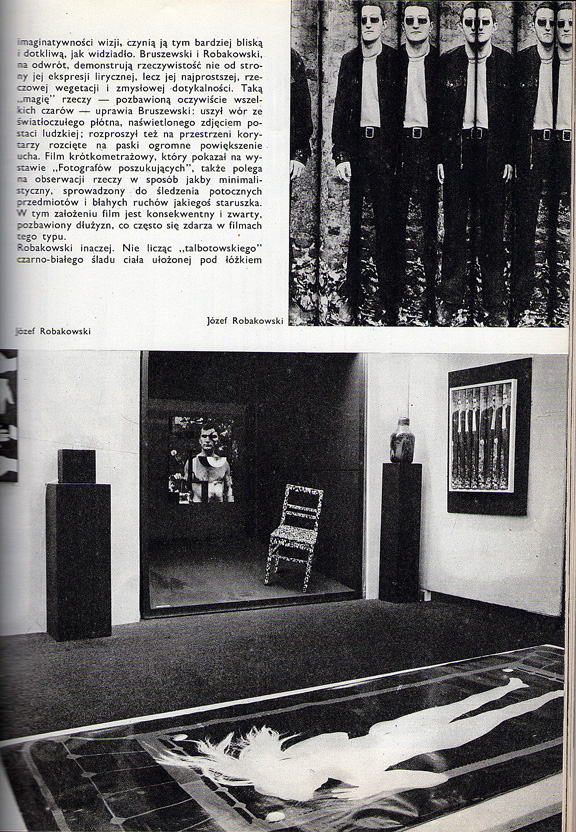

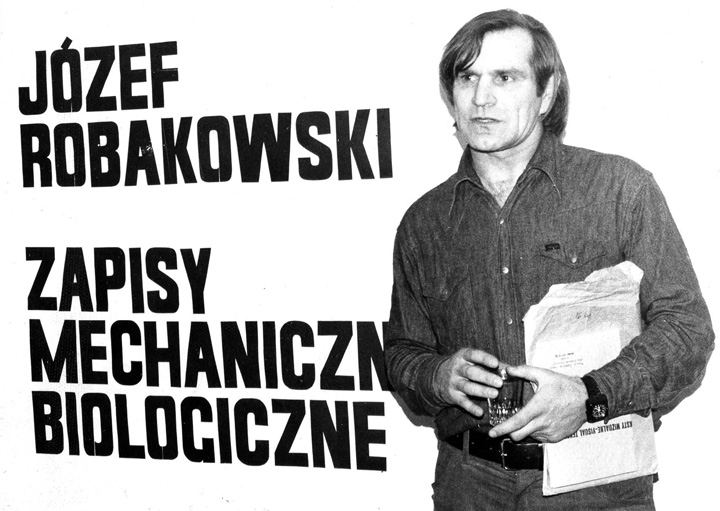

Stanisław Królak wygrał wyścig w 1952 i 1955 roku Stanisław Królak wygrał wyścig w 1952 i 1955 roku    Mała Galeria ZPAF, Warszawa, performance Łodzi Kaliskiej, 31.07.1984, fot. Paweł Całka Mała Galeria ZPAF, Warszawa, performance Łodzi Kaliskiej, 31.07.1984, fot. Paweł Całka Mała Galeria ZPAF, Warszawa, performance Łodzi Kaliskiej, 31.07.1984, fot. Paweł Całka Mała Galeria ZPAF, Warszawa, performance Łodzi Kaliskiej, 31.07.1984, fot. Paweł Całka Polish cinema of the seventies Polish cinema of the seventies Zero-61Zero-61 - awangardowa grupa fotograficzna działająca w Toruniu w latach 1961-1969. Jej członkami byli m.in.: Zero-61Zero-61 - awangardowa grupa fotograficzna działająca w Toruniu w latach 1961-1969. Jej członkami byli m.in.:- Czesław Kuchta- Jerzy Wardak- Józef Robakowski- Wiesław Wojczulanis- Andrzej Różycki- Antoni Mikołajczyk- Wojciech Bruszewski- Michał Kokot Grupa Artystyczna Zero-61: Andrzej Różycki, Józef Robakowski. Fot. Tadeusz Rolke. Grupa Artystyczna Zero-61: Andrzej Różycki, Józef Robakowski. Fot. Tadeusz Rolke. Grupa Artystyczna Zero-61: Andrzej Różycki, Czesław Kuchta, Józef Robakowski. Fot. Tadeusz Rolke. Grupa Artystyczna Zero-61: Andrzej Różycki, Czesław Kuchta, Józef Robakowski. Fot. Tadeusz Rolke. Grupa Artystyczna Zero-61: Wojciech Bruszewski, Józef Robakowski, Jerzy Wardak. Fot. Tadeusz Rolke. Grupa Artystyczna Zero-61: Wojciech Bruszewski, Józef Robakowski, Jerzy Wardak. Fot. Tadeusz Rolke. Grupa Artystyczna Zero-61: Wojciech Bruszewski i Józef Robakowski. Fot. Tadeusz Rolke. Grupa Artystyczna Zero-61: Wojciech Bruszewski i Józef Robakowski. Fot. Tadeusz Rolke. R eprodukcja strony z miesięcznika FOTOGRAFIA - fragment artykułu Urszuli Czartoryskiej "Czego fotografowie poszukują?" z numeru 6 (216) / 1971. Mała Galeria PSP-ZPAF, Warszawa , wystawa Józefa Robakowskiego "Zapisy mechaniczno - biologiczne", 28.04.1978, fot. Arch. Małej Galerii Mała Galeria PSP-ZPAF, Warszawa , wystawa Józefa Robakowskiego "Zapisy mechaniczno - biologiczne", 28.04.1978, fot. Arch. Małej Galerii Pokaz filmów J. Robakowskiego (przy projektorze) w Małej Galerii PSP - ZPAF w Warszawie, 20.05.1980, fot. Arch. Małej GaleriiWarsztat Formy Filmowej(1970 - 1977) Pokaz filmów J. Robakowskiego (przy projektorze) w Małej Galerii PSP - ZPAF w Warszawie, 20.05.1980, fot. Arch. Małej GaleriiWarsztat Formy Filmowej(1970 - 1977)  WARSZTAT FORMY FILMOWEJ: od lewej, górny rzad : Janusz Polom, Wojciech Bruszewski, Wacław Antczak, Jacek Łomnicki, Tadeusz Junak; niżej po lewej sylwetka : Zdzisław Sowiński; po prawej (łysy):Antoni Mikołajczyk; od lewej na dole : Lech Członowski, Józef Robakowski (w białym swetrze), Paweł Kwiek, Zbigniew Rybczyński, Andrzej Różycki, Ryszard Waśko. WARSZTAT FORMY FILMOWEJ: od lewej, górny rzad : Janusz Polom, Wojciech Bruszewski, Wacław Antczak, Jacek Łomnicki, Tadeusz Junak; niżej po lewej sylwetka : Zdzisław Sowiński; po prawej (łysy):Antoni Mikołajczyk; od lewej na dole : Lech Członowski, Józef Robakowski (w białym swetrze), Paweł Kwiek, Zbigniew Rybczyński, Andrzej Różycki, Ryszard Waśko.  pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Warsztat_Formy_FilmowejMariusz HermanowiczMariusz Hermanowicz pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Warsztat_Formy_FilmowejMariusz HermanowiczMariusz Hermanowicz was at the fringe of the neo-avantgarde. In his original, sarcastically ironic works, Hermanowicz commented on the grey reality of everyday life in communist Poland; later, he continued his work abroad. Martial law brought about the closure of many galleries, and many photographers and other artists who used photographic techniques in their work emigrated at this time.  Mariusz Hermanowicz Mariusz Hermanowicz  Mariusz Hermanowicz Mariusz Hermanowicz  Mariusz Hermanowicz Mariusz Hermanowicz  Mariusz Hermanowicz Mariusz Hermanowicz   1961 Eustachy i Matylda, photographer Tadeusz Rolke 1961 Eustachy i Matylda, photographer Tadeusz Rolke Fashion photo by Tadeusz Rolke Fashion photo by Tadeusz Rolke Fashion photo by Tadeusz Rolke Fashion photo by Tadeusz Rolke Photo Tadeusz Rolke Photo Tadeusz Rolke Tadeusz Rolke Warszawa, 1990/2013 Tadeusz Rolke Warszawa, 1990/2013  Photo: Tadeusz Rolke Photo: Tadeusz Rolke Gustaw Holoubek i Tadeusz Konwicki, photo: Tadeusz Rolke (Gazeta Wyborcza) Gustaw Holoubek i Tadeusz Konwicki, photo: Tadeusz Rolke (Gazeta Wyborcza) Małgorzata Braunek (30 January 1947 – 23 June 2014) Polish film and stage actress. Photo Tadeusz Konwicki Małgorzata Braunek (30 January 1947 – 23 June 2014) Polish film and stage actress. Photo Tadeusz Konwicki Małgorzata Braunek Małgorzata Braunek    Strikers' families on the other side of the gate (photo: B. Nieznalski/Karta). Strikers' families on the other side of the gate (photo: B. Nieznalski/Karta).   Anna Walentynowicz, one of the leaders of Solidarność, talks with Polish workersculture.pl/en/article/the-history-of-polish-photography Anna Walentynowicz, one of the leaders of Solidarność, talks with Polish workersculture.pl/en/article/the-history-of-polish-photography |

|

|

|

Post by Jaga on Aug 14, 2014 19:46:48 GMT -7

Pieter,

bravo! Very pointed and wonderful pictures

Stanislaw Krolak and his achielevents as a biker in Wyscig Pokoju were already legendary when I was young. He died in 2009 and he achieved his success in 50s.

The May 1st parade I remember from my highschool. I was the sign "liceum ogolnoksztalcace" at one of your pictures

Referring to Syrenka - the car produced in 60s, in spite of its weak quality everybody liked it....

I remember Zuk's, not sure they are still there on the roads.

Interesting and quite artistic pictures of a photographer, showing girls with a sense of fashion in grey Poland.

|

|

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)