|

|

Ukraine

Jan 15, 2022 6:02:51 GMT -7

Post by pieter on Jan 15, 2022 6:02:51 GMT -7

Ukrainian nationalism Ukrainian nationalism Ukrainian Nationalist march in Kyiv, UkraineUkrainian nationalism is the ideology promoting the unity of Ukrainians into their own nation state, Ukraine. Although the current Ukrainian state emerged fairly recently, some historians, such as Mykhailo Hrushevsky, Orest Subtelny, and Paul Robert Magocsi, cited the medieval state of Kyivan Rus as an early precedent of specifically Ukrainian statehood. The origins of modern Ukrainian nationalism are also traced to the 17th-century Cossack uprising against the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth led by the Ukrainian Cossack Hetman Zynoviy Bohdan Khmelnytsky (1595 – 1657). Khmelnytsky led an uprising against the Commonwealth and its magnates (1648–1654) that resulted in the creation of a state led by the Cossacks. This Cossack-Polish War, the Chmielnicki Uprising, the Khmelnytsky massacre or the Khmelnytsky insurrection, was an Ukrainian Cossack rebellion that took place between 1648 and 1657 in the eastern territories of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, which led to the creation of a Cossack Hetmanate in Ukraine. Ukrainian Nationalist march in Kyiv, UkraineUkrainian nationalism is the ideology promoting the unity of Ukrainians into their own nation state, Ukraine. Although the current Ukrainian state emerged fairly recently, some historians, such as Mykhailo Hrushevsky, Orest Subtelny, and Paul Robert Magocsi, cited the medieval state of Kyivan Rus as an early precedent of specifically Ukrainian statehood. The origins of modern Ukrainian nationalism are also traced to the 17th-century Cossack uprising against the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth led by the Ukrainian Cossack Hetman Zynoviy Bohdan Khmelnytsky (1595 – 1657). Khmelnytsky led an uprising against the Commonwealth and its magnates (1648–1654) that resulted in the creation of a state led by the Cossacks. This Cossack-Polish War, the Chmielnicki Uprising, the Khmelnytsky massacre or the Khmelnytsky insurrection, was an Ukrainian Cossack rebellion that took place between 1648 and 1657 in the eastern territories of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, which led to the creation of a Cossack Hetmanate in Ukraine.

Massacre of 3000–5000 bound Polish captives after the battle of Batih in 1652 carried out by Ukrainian Cossacks under the command of Hetman Bohdan Khmelnytsky

Zynoviy Bohdan Khmelnytsky (Ruthenian: Ѕѣнові Богдан Хмелнiцкiи; modern Ukrainian: Богдан Зиновій Михайлович Хмельницький; c. 1595 – 6 August 1657) was a Ukrainian Hetman of the Zaporozhian Host, then in the Polish Crown of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (now part of Ukraine). He led an uprising against the Commonwealth and its magnates (1648–1654) that resulted in the creation of a state led by the Cossacks. In 1654, he concluded the Treaty of Pereyaslav with the Moscow Tsar and thus allied the Cossack Hetmanate with Tsardom of Muscovy.

Mykhailo Serhiiovych Hrushevsky (Ukrainian: Михайло Сергійович Грушевський, Chełm, 29 September [O.S. 17 September] 1866 – Kislovodsk, 24 November 1934) was a Ukrainian academician, politician, historian and statesman who was one of the most important figures of the Ukrainian national revival of the early 20th century.

Folks, in my opinion the extreme Ultra-Nationalist Banderist form of Ukrainian Nationalism has a strong anti-Russian, anti-Polish, anti-Hungarian, anti-Romanian, anti-Moldovan and anti-semitic sentiments. Pan-Slavic, Greek Catholic and Ukrainian Orthodox christian identities play a role in that. The ethnic Eastern-slavic, Orthodox Christian, Byzantian, Ukrainian distinct National identity. And that identity exist in an antithesis with the Polish and Russian ethnic, cultural and religious identity. Being Ukrainian means being Not-Polish, Not-Russian, Not-Belarussian, Not Hungarian, Not Bessarabian (Moldovan), Not Romanian, Not Bulgarian, Not Turkish, Not Jewish, Not Georgian, Not Tartar, Not Armenian, Not Siberian, not Moscow oriented and certainly not West-European, but in the same time Pro-EU and Pro-NATO. Ukrainians are Ukrainians. The Ukrainian peasents serfs in the Feudal Serfdom system of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and Czarist Russia had and have an aversion towards the Western Slav, Roman Catholic and ethnic Polish Magnates, Schlachta and Polish Jews in Ukraine. And later in the independent Ukraine of the nineties and the 21th century these Ukrainian Ultra-nationalist Banderivtsi (Ukrainian: Бандерівці, Bandе́rivtsi or bandе́rovtsy, Polish: banderowcy, Russian: Бандеровцы) have an aversion towars a Polish minority in Western-Ukraine which kept a Polish identity, their Polish language, Polish culture and Roman-Catholic faith like the Polish minorities in Belarus and Lithuania. The same counts for the in their eyes non-Slavic Hungarians, Romanians, Moldovans and the Romani-, Karaite- and Tartar minorities in Ukraine. Hetman Ivan Mazepa (1639-1709), a prominent figure in Cossack nationalism, made large financial contributions focused on the restoration of Ukrainian culture and history during the early 18th century. He financed major reconstructions of the Saint Sophia Cathedral in Kyiv, and the elevation the Kyiv Mohyla Collegium to the status of Kyiv Mohyla Academy in 1694. Politically, Mazepa was misunderstood and misrepresented, and found little support among the peasantry.

Ivan Stepanovych Mazepa (also spelled Mazeppa; Ukrainian: Іван Степанович Мазепа, Polish: Jan Mazepa Kołodyński; 30 March [O.S. 20 March] 1639 – 2 October [O.S. 21 September] 1709) served as the Hetman of Zaporizhian Host in 1687–1708. He was awarded a title of Prince of the Holy Roman Empire in 1707 for his efforts for the Holy League. The historical events of Mazepa's life have inspired many literary, artistic and musical works. He was famous as a patron of the arts.

Mazepa played an important role in the Battle of Poltava (1709), where after learning that Tsar Peter I intended to relieve him as acting Hetman (military leader) of Zaporizhian Host (a Cossack state) and to replace him with Alexander Menshikov, he deserted his army and sided with King Charles XII of Sweden. The political consequences and interpretation of this desertion have resonated in the national histories both of Russia and of Ukraine.

The Russian Orthodox Church laid an anathema (excommunication) on Mazepa's name in 1708 and still refuses to revoke it. Anti-Russian elements in Ukraine from the 18th century onwards were derogatorily referred to as Mazepintsy (Mazepists). The alienation of Mazepa from Ukrainian historiography continued during the Soviet period, but post-1991 in independent Ukraine there have been strong moves to rehabilitate Mazepa's image, although some still regard him as a controversial figure.

Another Great Ukrainian in the eyes of some Ukrainian nationalists is the Ukrianian Cossack political and military leader Petro Doroshenko, Hetman of Right-bank Ukraine (1665–1672) and a Russian voyevoda (voivodeship). Some consider him a national hero who wanted an independent Ukraine, while to others he was a power-hungry Cossack Hetman who offered Ukraine to a Muslim Sultan in exchange for hereditary overlordship of his native land.

In the fall of 1667, with support of Crimean Tatars, the Ukrainain Hetman Petro Doroshenko defeated the Polish forces at the Battle of Brailiv (Brailiv) in Podolia. After the battle, Doroshenko's opposition, led by the Kosh Otaman Ivan Sirko and Tatars stopped his further advance against Poles. With the Right-Bank seemingly secured, Doroshenko and his men crossed into Left-bank Ukraine and supported an uprising of Ivan Briukhovetsky against Muscovy.

Supported by Crimean Tatars and Ottoman Turkey in 1665, Doroshenko crushed the pro-Russian Cossack bands and eventually became Hetman of Ukraine (Right-bank Ukraine).

Petro Doroshenko (Ukrainian: Петро Дорофійович Дорошенко, Russian: Пётр Дорофе́евич Дороше́нко, Polish: Piotr Doroszenko; 1627–1698) was a Cossack political and military leader, Hetman of Right-bank Ukraine (1665–1672) and a Russian voyevoda.

So there is a very nasty side, a dark side to Ukrainian nationalism which goes back to the Khmelnytsky Uprising of 1648–1657, and a series of pogroms against Jews in the city of Odessa, Ukraine, then part of the Russian Empire, took place during the 19th and early 20th centuries. They occurred in 1821, 1859, 1871, 1881 and 1905. The series of pogroms in Ukraine in 1905; in Elizabethgrad (April 27, 28), Kiev (May 8–11), Shpola (May 9), Ananiv (May 9), Wasilkov (May 10) and Konotop (May 10). During the Russian Civil war from 7 November 1917 until 16 June 1923 between White and Red armies in Ukraine a lot of civilians were murdered by White Army, Russian Red Army, Social Revolutionary Party members, the Ukrainian Black army and other armed groups, militia and armies. The Revolutionary Insurrectionary Army of Ukraine (Ukrainian: Революційна Повстанська Армія України), also known as the Black Army or as Makhnovtsi (Ukrainian: Махновці), named after their leader Nestor Makhno, was an anarchist army formed largely of Ukrainian peasants and workers during the Russian Civil War of 1917–1922. They protected the operation of "free soviets" and libertarian communes in the Free Territory, an attempt to form a stateless libertarian communist society from 1918 to 1921 during the Ukrainian War of Independence. They were founded and inspired based on the Black Guards.

A flag used by the 2nd Consolidated Infantry Regiment of the RIAU

Nestor Ivanovych Makhno (7 November [O.S. 26 October] 1888 – July 25, 1934), commonly known as Bat'ko Makhno (Ukrainian: батько Махно; ˈbɑtʲko mɐxˈnɔ, "Father Makhno"), was a Ukrainian anarchist revolutionary and the commander of an independent anarchist army in Ukraine from 1917 to 1921.

Other events that shaped Ukrainian Nationalism and Patriotism

The Kyiv Pogroms of 1919 were splurges of looting, raping, and murder chiefly directed against the shops, factories, homes, and persons of the Jews. The Polish–Ukrainian War (Wojna polsko-ukraińska), from November 1918 to July 1919, the assassination of Tadeusz Ludwik Hołówko (September 17, 1889 – August 29, 1931), a Polish promoter of Ukrainian/Polish compromise, by militants of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) on August 29, 1931 in Truskawiec, in the Drohobycz County of the Lwów Voivodeship in Poland (today situated in the Lviv Oblast [Province] in Ukraine), and the assassination of the Polish minister of internal affairs Bronisław Wilhelm Pieracki (28 May 1895 in Gorlice – 15 June 1934 in Warsaw) on 15 June 1934, Pieracki was assassinated by a member of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists. Some of the OUN's victims included Emilian Czechowski, Lwow's Polish police commissioner, and Alexei Mailov, a Soviet consular official killed in retaliation for the Holodomor. From 1921 to 1939 UVO (Ukrainian Military Organization) and OUN (the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists) carried out 63 known assassinations: 36 Ukrainians (among them one communist), 25 Poles, 1 Russian and 1 Jew. This number is likely an underestimate, because there were likely unrecorded killing in rural regions. The Ukrainian Military Organization (Ukrainian: Українська Військова Організація, UVO) was a Ukrainian paramilitary organization which engaged in terrorism, active in Eastern Galicia (then in Poland) during the interwar period. It was formed after occupation of Ukraine by the Soviet Russia following the Ukrainian–Soviet War and the Peace of Riga that divided Ukraine between Poland and the Soviet Union. Initially headed by Yevhen Konovalets, the organization promoted the idea of armed struggle for the independence of Ukraine. The headquarters of the organization was located in Lwów (today Lviv, Ukraine) Second Polish Republic. The death of Bronisław Pieracki gave Poland's Sanation government a justification to create, two days after the assassination, the Bereza Kartuska Prison. The prison's first detainees were almost entirely the leadership of the Polish nationalist far-right National Radical Camp (the ONR), arrested on 6–7 July 1934. Sentenced to death for the Pieracki assassination were Stepan Bandera and Mykola Lebed. Their sentences were commuted to life imprisonment, and Lebed escaped when Germany invaded Poland in 1939. In the Bereza Kartuska Prison inmates were detained without trial or conviction, it is considered an internment camp or concentration camp. Bereza Kartuska Prison was established on 17 June 1934 by order of President Ignacy Mościcki to detain persons who were viewed by the Polish state as a "threat to security, peace, and social order" or alternately to isolate and demoralize political opponents of the Sanation government (Sanacja) such as the National Democrats of Roman Stanisław Dmowski (9 August 1864 – 2 January 1939), members of the far-right National Radical Camp (the ONR), ONR-Falanga (Ruch Narodowo-Radykalny), National Radical Camp ABC (Polish: Obóz Narodowo-Radykalny ABC), Polish communists (Polish: Komunistyczna Partia Polski, KPP [1918-1938]), members of the Polish People's Party, members of the Polish Socialist Party (PPS) and Ukrainian and Belarusian nationalists.

Tadeusz Ludwik Hołówko (September 17, 1889 – August 29, 1931), codename Kirgiz, was an interwar Polish politician, diplomat and author of many articles and books. Tadeusz Hołówko was assassinated on August 29, 1931, and was one of the first victims of an assassination campaign carried out by militants of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) against moderate Ukrainians and Polish officials.

Emilian Czechowski (ur. 18 lipca 1884 w Buczaczu, zm. 22 marca 1932 we Lwowie) – podkomisarz Policji Państwowej.

Bronisław Wilhelm Pieracki (28 May 1895 in Gorlice – 15 June 1934 in Warsaw) was a Polish military officer and politician. As a member of Polish Legions in World War I, Pieracki took part in the Polish-Ukrainian War (1918–1919) and he later supported the 1926 May Coup of Józef Piłsudski. Pieracki was a deputy in the Polish Sejm from the Nonpartisan Bloc for Cooperation with the Government in 1928 and afterwards deputy Chief of Staff. On 15 June 1934, Pieracki was assassinated by a member of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists.

Yevhen Mykhailovych Konovalets (June 14, 1891 – May 23, 1938) was a military commander of the Ukrainian National Republic army, veteran of the Ukrainian-Soviet War and political leader of the Ukrainian nationalist movement. He is best known as the leader of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists between 1929 and 1938.

The armed conflict between between the Polish Home Army (Polish: Armia Krajowa) and the military arm of Stepan Bandera's faction of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists - Revolutionary (OUN-R), the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA) in the period 1943–1945, the massacres of Poles in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia (Polish: rzeź wołyńska, literally: Volhynian slaughter; Ukrainian: Волинська трагедія, Volyn tragedy), carried out in German-occupied Poland by the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA) in 1943 the German-Austrian Nazi-occupied territories. Next to the Ukrainain Petro Dyachenko's 31. Schutzmannschaft-Bataillon des SD involvement in oppressing the Warsaw Rising (August-October 1944), together with the men of the notorious Nazi war criminal SS-Oberführer Oskar Paul Dirlewanger (26 September 1895 – c. 7 June 1945) of the SS-Sturmbrigade "Dirlewanger" and the SS Sturmbrigade RONA under the command of SS-Brigadeführer Bronislav Kaminski (16 June 1899 – 28 August 1944), the Ukrainian 14th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS (1st Galician) involvement in the Second World War and the brutal Ukrainian kapo's or prisoner functionaries (German: Funktionshäftling), prisoners in a Nazi camp who were assigned by the German and Austrian SS-Totenkopfverbände (SS-TV) guards, the SS organization responsible for administering the Nazi concentration camps and extermination camps for Nazi Germany to supervise forced labor or carry out administrative tasks. Many Ukrainian prisoner functionaries (Kapo's) were recruited from the ranks of violent criminal gangs rather than from the more numerous political, religious, and racial prisoners; such criminal convicts were known for their brutality toward other prisoners. This brutality was tolerated by the SS and was an integral part of the camp system. An eager prisoner functionary (Kapo) could have a camp "career" as an SS favorite and be promoted from Kapo to Oberkapo and eventually to Lagerältester, but he could also just as easily run afoul of the SS and be sent to the gas chambers. Many Kapos very quickly gained the reputation of brutal supervisors, beating, denouncing and even killing fellow inmates. Physical and sexual abuse were commonplace. Needless to say, this was not true of all Kapos. Some used their positions to support and protect, even to save the lives of others. If they were caught doing this or unable to perform their duties, they were dismissed, punished and henceforth treated as ordinary prisoners. Ukrainians were amongst the most notorious Kapo's, guards and also as sadistic Ukrainian police in some Jewish Ghetto's in German/Austrian Nazi occupied Central- and Eastern-Europe. Next to this the Ukrainian Auxiliary Police were the major perpetrator of the Holocaust on Soviet territories based on native origins, and those police units participated in the extermination of 150,000 Jews in the area of Volhynia alone.

Massacred Polish women, men and children in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia, murdered in German-occupied Poland by the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA) in 1943 in the German-Austrian Nazi-occupied territories

Poles - victims of the OUN (b) 26 March action 1943 of the year in the now defunct Lipniki village

Naked Jewish women, some of whom are holding infants, wait in a line before their execution by German Sipo and SD with the assistance of the Ukrainian Auxiliary Police. The Mizocz Ghetto, 13 October 1942.

Polish Ukrainians struggle in the period 1943-1945

Official oath of partisans- soldiers of 27th Home Army Infantry Division, Volhynia winter 1944

In the Southeastern part of occupied Polish territories, there have been long-standing tensions between the Polish and Ukrainian populations. Poland's plans to restore its prewar borders were opposed by the Ukrainians, and some Ukrainian groups' collaboration with Nazi Germany had discredited their partisans as potential Polish allies. While the Polish government-in-exile considered tentative plans about providing a limited autonomy for Ukrainians, in 1942 the staff of the Home Army of Lviv recommended deporting 1–1.5 million Ukrainians to the Soviet Union and settling the remainder in other parts of Poland once the war ended. The situation escalated the next year when the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (Українська повстанська армія, Ukrayins'ka Povstans'ka Armiya, UPA), a Ukrainian nationalist force and the military arm of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (Організація Українських Націоналістів, Orhanizatsiya Ukrayins'kykh Natsionalistiv, OUN), directed most of its attacks against Poles and Jews. Stepan Bandera, one of UPA's leaders, and his followers concluded that the war would end in the exhaustion of both Germany and the Soviet Union, leaving only the Poles—who laid claim to East Galicia (viewed by the Ukrainians as western Ukraine, and by the Poles as Kresy)—as a significant force, and therefore the Poles had to be weakened before the war's end.

Members of the UPA (Ukrainian Insurgent Army, the armed wing of Stepan Bandera's OUN-B organisation) in Volhynia

The OUN decided to attack Polish civilians, who constituted about a third of the population of the disputed territories. It equated Ukrainian independence with ethnic homogeneity, which meant the Polish presence had to be completely removed. By February 1943 the OUN began a deliberate campaign of killing Polish civilians. In massacres of Poles in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia, beginning in the spring of 1943, 100,000 Poles were killed. OUN forces targeted Polish villages, which prompted the formation of Polish self-defense units (e.g., the Przebraże Defence) and fights between the Home Army and the OUN. The Germans encouraged both sides against each other; Erich Koch said: "We have to do everything possible so that a Pole, when meeting a Ukrainian, will be ready to kill him, and conversely, a Ukrainian will be ready to kill the Pole." A German commissioner from Sarny, when local Poles complained about massacres, answered: "You want Sikorski, the Ukrainians want Bandera. Fight each other." On 10 July 1943, Zygmunt Rumel was sent to talk with local Ukrainians with the goal of ending the massacres; the mission was unsuccessful, and the Banderites killed the Polish delegation. On 20 July that year the Home Army command decided to establish partisan units in Volhynia. Several formations were created, most notably, in January 1944, the 27th Home Army Infantry Division. Between January and March 1944, the division fought 16 major battles with the UPA, expanding its operational base and securing Polish forces against the main attack. One of the largest battles between the Home Army and the UPA took place in Hanaczów [pl], where local self-defence forces managed to fend off two attacks. In March 1944 the Home Army also carried out reprisal attack against UPA in the village of Sahryń, remembered as "Sahryń massacre", ended in ethnic cleansing operations in which about 700 Ukrainian civilians were killed.

The Polish government-in-exile in London was taken by surprise; it did not expect Ukrainian anti-Polish actions of such magnitude. There is no evidence that the Polish government-in-exile contemplated a general policy of revenge against the Ukrainians, but local Poles, including Home Army commanders, engaged in retaliatory actions. Polish partisans attacked the OUN, assassinated Ukrainian commanders, and carried out operations against Ukrainian villages. Retaliatory operations aimed at intimidating the Ukrainian population contributed to increased support for the UPA. The Home Army command tried to limit operations against Ukrainian civilians to a minimum. According to Grzegorz Motyka, the Polish operations resulted in 10,000 to 15,000 Ukrainian deaths in 1943–47, including 8,000-10,000 on territory of post-war Poland. From February to April 1945, mainly in Rzeszowszczyzna (the Rzeszów area), Polish units (including affiliates of the Home Army) carried out retaliatory attacks in which about 3,000 Ukrainians were killed; one of the most infamous ones is known as the Pawłokoma massacre.

By mid-1944, most of the disputed regions were occupied by the Soviet Red Army. Polish partisans disbanded or went underground, as did most Ukrainian partisans. Both the Poles and the Ukrainians would increasingly concentrate on the Soviets as their primary enemy – and both would ultimately fail.

Massacres of Poles in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia

In 1943, the UPA adopted a policy of massacring and expelling the Polish population. The ethnic cleansing operation against the Poles began on a large scale in Volhynia in late February (or early Spring) of that year and lasted until the end of 1944. 11 July 1943 was one of the deadliest days of the massacres, with UPA units marching from village to village, killing Polish civilians. On that day, UPA units surrounded and attacked 99 Polish villages and settlements in three counties: 1) - Kowel, 2) - Horochów, and 3) - Włodzimierz Wołyński. On the following day 50 additional villages were attacked. In January 1944, the UPA campaign of ethnic cleansing spread to the neighbouring province of Galicia. Unlike in Volhynia, where Polish villages were destroyed and their inhabitants murdered without warning, Poles in eastern Galicia were in some instances given the choice of fleeing or being killed. Ukrainian peasants sometimes joined the UPA in the violence, and large bands of armed marauders, unaffiliated with the UPA, brutalized civilians. In other cases however, Ukrainian civilians took significant steps to protect their Polish neighbours, either by hiding them during the UPA raids or vouching that the Poles were actually Ukrainians.

The methods used by UPA to carry out the massacres were particularly brutal and were committed indiscriminately without any restraint. Historian Norman Davies describes the killings: "Villages were torched. Roman Catholic priests were axed or crucified. Churches were burned with all their parishioners. Isolated farms were attacked by gangs carrying pitchforks and kitchen knives. Throats were cut. Pregnant women were bayoneted. Children were cut in two. Men were ambushed in the field and led away." In total, the estimated numbers of Polish civilians killed by UPA in Volhynia and Galicia is about 100,000. On 22 July 2016, the Sejm of the Republic of Poland passed a resolution declaring the massacres committed by UPA a genocide.

The child in the photo – is 2-year old, Czeslaw Chrzanowska from the Kuta village (Kosovskiy region IvanoFrankivsk, West Ukraine). This is her last photo. In April 1944 the Kuta village is attacked by Stepan Bandera men of the armed wing of his OUN-B organisation, soldiers and officers of the UPA (Ukrainian Insurgent Army). Sleeping in the night Cheslava is stabbed by a bayonet in a baby cot.

The girl at the center Stacya Stephanek is killed in a horrific way – her belly is cut because her father is a Pole. Regardless of her mother Mary Boyarchuk being a Ukrainian, that night she is killed too. Because she married a Pole.

Stepan Andriyovych Bandera (Ukrainian: Степан Андрійович Бандера, Polish: Stepan Andrijowycz Bandera; 1 January 1909 – 15 October 1959) was a Ukrainian politician and theorist of the militant wing of the far-right Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists and a leader and ideologist of Ukrainian ultranationalists known for his involvement in terrorist activities. Today Ukrainian Nationalists, Neo-Fascists, Neo-Nazi's and Pan-Slavists are still Bandera supporters and are called by Ukrainians, Russian and Poles Banderites.

Banderites

Stepan Bandera's face looks down from his statue in Kyiv and his face looms out of frames held aloft by champions as diverse as the far right neo-fascists of Right Sector and Svoboda, and the liberal pro-European activists pounding the Kiev streets in protest.

The Banderivtsi (Ukrainian: Бандерівці, Bandе́rivtsi or bandе́rovtsy, Polish: banderowcy, Russian: Бандеровцы) are members of an assortment of right-wing organizations in Ukraine.

The term derives from the name of Stepan Bandera (1909-1959), head of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) that formed in 1929 as an amalgamation of movements including the Union of Ukrainian Fascists. The union, known as OUN-B, had been engaged in various atrocities, including murder of civilians, most of whom were ethnic Poles. This was the result of the organization's extreme Polonophobia (anti-Polonism, anti-Polish sentiment), but the victims also included other minorities such as Jews and Romani people. The term "Banderites" was used by Bandera followers themselves, by others during the Holocaust, and during the massacres of Poles in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia by OUN-UPA from 1943–1944. These massacres resulted in the deaths of 80,000-100,000 Poles and 10,000-15,000 Ukrainians.

Ukrainian and Lithuanian nationalists utilized the increasing racial segregation to foment anti-Polonism. Followers of Stepan Bandera (also called Banderovites) committed genocide on Poles in Volhynia at 1943. Lithuanian forces often clash with Polish forces throughout the World War II, and committed massacres on Poles with support from the Nazis.

According to Timothy D. Snyder, the term continues to be used (often pejoratively) to describe Ukrainian nationalists who sympathize with fascist ideology and consider themselves followers of the OUN-UPA myth in modern Ukraine.

Stepan Bandera monument in Ternopil, a city in western Ukraine

A number of contemporary far-right Ukrainian political organizations claim to be inheritors of the OUN's (the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists) political traditions, including far right Ultra Nationalist Ukrainian Nationalist Svoboda party, the Ukrainian ultranationalist, Neo-Fascist and Hard Eurosceptic Right Sector, the Ukrainian fascist and Pan-Slavist Ukrainian National Assembly – Ukrainian National Self Defence, the Far right Ukrainian Nationalist Congress of Ukrainian Nationalists and the Ultra-nationalist and anti-Russian National Corps.

Late March 2019 former OUN combatants (and other living former members of irregular Ukrainian nationalist armed groups that were active during World War II and the first decade after the war) were officially granted the status of veterans. This meant that for the first time they could receive veteran benefits, including free public transport, subsidized medical services, annual monetary aid, and public utilities discounts (and will enjoy the same social benefits as former Ukrainian soldiers Red Army of the Soviet Union). Banderivtsi during a nationalist Ukrainian demonstration in Kyiv Banderivtsi during a nationalist Ukrainian demonstration in Kyiv Activists and supporters of Ukrainian nationalist parties hold torches as they take part in a rally to mark the 112th birth anniversary of Stepan Bandera, in Kyiv, Ukraine, January 1, 2021. Credit: Valentyn Ogirenko/Reuters In present-day Ukraine Activists and supporters of Ukrainian nationalist parties hold torches as they take part in a rally to mark the 112th birth anniversary of Stepan Bandera, in Kyiv, Ukraine, January 1, 2021. Credit: Valentyn Ogirenko/Reuters In present-day Ukraine Lviv football fans at a 2010 game against Donetsk. The banner reads "Bandera – our hero."In the first decade of the 21st century, voters from Western Ukraine and Central Ukraine tended to vote for pro-Western and pro-European general liberal national democrats, while pro-Russian parties got the vote in Eastern Ukraine and Southern Ukraine. From the 1998 Ukrainian parliamentary election until the 2012 Ukrainian parliamentary election, no nationalist party obtained seats in the Verkhovna Rada (Ukraine's parliament). In these elections, nationalist right-wing parties obtained less than 1% of the votes; in the 1998 parliamentary election, they obtained 3.26%. Lviv football fans at a 2010 game against Donetsk. The banner reads "Bandera – our hero."In the first decade of the 21st century, voters from Western Ukraine and Central Ukraine tended to vote for pro-Western and pro-European general liberal national democrats, while pro-Russian parties got the vote in Eastern Ukraine and Southern Ukraine. From the 1998 Ukrainian parliamentary election until the 2012 Ukrainian parliamentary election, no nationalist party obtained seats in the Verkhovna Rada (Ukraine's parliament). In these elections, nationalist right-wing parties obtained less than 1% of the votes; in the 1998 parliamentary election, they obtained 3.26%.

The nationalist party Svoboda had an electoral breakthrough with the 2009 Ternopil Oblast local election, when they obtained 34.69% of the votes and 50 seats out of 120 in the Ternopil Oblast Council. This was the best result for a far-right party in Ukraine’s history. In the previous 2006 Ternopil Oblast local election, the party had obtained 4.2% of the votes and 4 seats. In the simulatenous 2006 Ukrainian local elections for the Lviv Oblast Council, it had obtained 5.62% of the votes and 10 seats and 6.69% of the votes and 9 seats in the Lviv city council. In 1991, Svoboda was founded as the Social-National Party of Ukraine. The party combined radical nationalism and alleged neo-Nazi features. Under Oleh Tyahnybok, it was renamed and rebranded in 2004 as the All-Ukrainian Association Svoboda. Political scientists Olexiy Haran and Alexander J. Motyl contend that Svoboda is radical rather than fascist and they also argue that it has more similarities with far-right movements like the Tea Party movement than it has with either fascists or neo-Nazis.

Oleh Yaroslavovych Tyahnybok (Ukrainian: Оле́г Яросла́вович Тягнибо́к, born 7 November 1968) is a Ukrainian politician who is a former member of the Verkhovna Rada and the leader of the Ukrainian nationalist far-right Svoboda political party. Previously, he was elected councilman of the Lviv Oblast Council for the second session.

In 2005, Victor Yushchenko appointed Volodymyr Viatrovych head of the Ukrainian security service (SBU) archives. According to professor Per Anders Rudling, this not only allowed Viatrovych to sanitize ultra-nationalist history but also to officially promote its dissemination along with OUN(b) ideology, which is based on "ethnic purity" coupled with anti-Russian, anti-Polish, and antisemitic rhetoric. The extreme right-wing now capitalizes on Yushchenkoist propaganda initiatives. This includes Iuryi Mykhal'chyshyn, an ideologue who proudly confesses that he is a part of the fascist tradition.[56]: 240 The autonomous nationalists focus on recruiting young people, participating in violent actions, and advocating "anti-bourgeoism, anti-capitalism, anti-globalism, anti-democratism, anti-liberalism, anti-bureaucratism, anti-dogmatism." Rulig suggested that Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych, sworn in on 25 February 2010, "indirectly aided Svoboda" by "granting Svoboda representatives disproportionate attention in the media."

In the 2010 Ukrainian local elections, Svoboda achieved notable success in Eastern Galicia.[58] In the 2012 parliamentary election, Svoboda came in fourth with 10,44% (almost a fourteenfold of its votes compared with the 2007 Ukrainian parliamentary election) of the national votes and 38 out of 450 seats. Following the 2012 parliamentary election, Batkivshchyna and UDAR cooperated officially with Svoboda. Fans of FC Karpaty Lviv honoring the Waffen-SS Galizien division, 2013  Euromaidan activists wave Ukraine's official flag, the flag of the Ukrainian People's Self-Defense and a red and black flag used by multiple nationalist organizations vying for Ukraine's independence after both World Wars; it dates back all the way to Ukraine's 16th century, March 2014.During and after the Russian military intervention in Ukraine, Russian media attempted to portray the Ukrainian party in the conflict as neo-Nazi. The main Ukrainian organisations involved with a neo-Banderaite legacy are Svoboda, Right Sector, and Azov Battalion. The Azov Battalion is led by Andriy Biletsky, the head of the ultra-nationalist and neo-Banderaite political groups Social-National Assembly and Patriots of Ukraine, is commander of the Azov Battalion and the Azov Battalion is part of the Ukrainian National Guard fighting pro-Russian separatists in the War in Donbass. According to a report in The Daily Telegraph, some individual anonymous members of the battalion identified themselves as sympathetic to the Third Reich. In June 2015, Democratic Representative John Conyers and his Republican colleague Ted Yoho offered bipartisan amendments to block the U.S. military training of Ukraine's Azov Battalion. Euromaidan activists wave Ukraine's official flag, the flag of the Ukrainian People's Self-Defense and a red and black flag used by multiple nationalist organizations vying for Ukraine's independence after both World Wars; it dates back all the way to Ukraine's 16th century, March 2014.During and after the Russian military intervention in Ukraine, Russian media attempted to portray the Ukrainian party in the conflict as neo-Nazi. The main Ukrainian organisations involved with a neo-Banderaite legacy are Svoboda, Right Sector, and Azov Battalion. The Azov Battalion is led by Andriy Biletsky, the head of the ultra-nationalist and neo-Banderaite political groups Social-National Assembly and Patriots of Ukraine, is commander of the Azov Battalion and the Azov Battalion is part of the Ukrainian National Guard fighting pro-Russian separatists in the War in Donbass. According to a report in The Daily Telegraph, some individual anonymous members of the battalion identified themselves as sympathetic to the Third Reich. In June 2015, Democratic Representative John Conyers and his Republican colleague Ted Yoho offered bipartisan amendments to block the U.S. military training of Ukraine's Azov Battalion.

Members of the Ultranationalist far right Right Sector

Members of the Ultranationalist far right Right Sector

After President Yanokovych's ouster in the February 2014 Ukrainian revolution, the interim Yatsenyuk Government placed four Svoboda members in leading positions; Oleksandr Sych as Vice Prime Minister of Ukraine, Ihor Tenyukh as Minister of Defense, lawyer Ihor Shvaika as Minister of Agrarian Policy and Food, and Andriy Mokhnyk as Minister of Ecology and Natural Resources of Ukraine. In a 5 March 2014 fact sheet, the U.S. State Department stated that "far-right wing ultranationalist groups, some of which were involved in open clashes with security forces during the Euromaidan protests, are not represented in the Ukrainian parliament."

In the 2014 Ukrainian presidential election and 2014 Ukrainian parliamentary election, Svoboda candidates failed to meet the electoral threshold to win. The party won six constituency seats in the 2014 parliamentary election and obtained 4.71% of national election list votes. In the 2014 presidential election, Svoboda leader Oleh Tyahnybok received 1.16% of the vote. Right Sector leader Dmytro Yarosh gained 0.7% of the votes in the 2014 presidential election, and was elected to parliament in the 2014 parliamentary election as a Right Sector candidate by winning a single-member district. Right Sector spokesperson Boryslav Bereza as an independent candidate also won a seat and district.

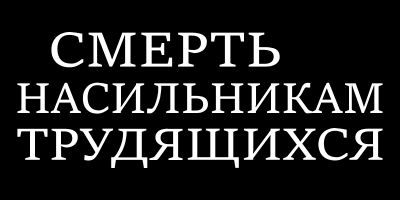

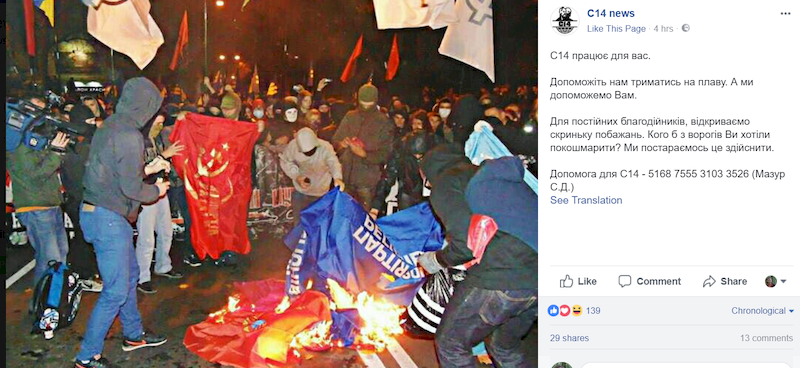

The radical nationalists group С14, whose members openly expressed neo-Nazi views, gained notoriety in 2018 for being involved in violent attacks on Romany camps. On 19 November 2018, Svoboda and fellow Ukrainian nationalist political organizations Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, Congress of Ukrainian Nationalists, Right Sector, and C14 endorsed Ruslan Koshulynskyi's candidacy in the 2019 Ukrainian presidential election. In the election, he received 1.6% of the votes. In the 2019 Ukrainian parliamentary election, a united party list with the nationalist right-wing parties Svoboda, Right Sector, Governmental Initiative of Yarosh, and National Corps won not enough votes to clear the 5% election threshold, they won 2.15% of the vote, and thus no parliamentary seats. Svoboda did win one constituency seat in the election. Boryslav Bereza and Dmytro Yarosh lost their parliamentary seats.

Members of radical nationalist group С14 in Ukraine

Folks from a diplomatic, historical, political, ethnic, religious and Financial-economical and geopolitical position I understand the situation. I understand the Russian feeling of defeat when the territory of both their great Soviet Empire with a Russian domination and the former territory of the Czarist Empire was lost in the sense of Unity of the Eastern slavs Russians, Ukrainians and Belarussions in one Great Empire. The old roots, heritage and idenity of Kievan Rus' plays a role here. Kievan Rus' or Kyivan Rus', was a loose federation of East Slavic, Baltic and Finnic peoples in Eastern and Northern Europe from the late 9th to the mid-13th century, under the reign of the Rurik dynasty, founded by the Varangian prince Rurik. The modern nations of Belarus, Russia, and Ukraine all claim Kievan Rus' as their cultural ancestors, with Belarus and Russia deriving their names from it.

Many Russians feel a connection to Great Russia, sometimes Great Rus' (Russian: Великая Русь, Velikaya Rus', Великая Россия, Velikaya Rossiya, Великороссия, Velikorossiya), the name formerly applied to the territories of "Russia proper", the land that formed the core of Muscovy and later Russia. This was the land to which the ethnic Russians were native and where the ethnogenesis of (Great) Russians took place. The name is said to have come from the Greek Μεγάλη Ῥωσ(σ)ία, Megálē Rhōs(s)ía used by Byzantines for the northern part of the lands of Rus'.

A fully independent Ukraine emerged only late in the 20th century, after long periods of successive domination by Poland-Lithuania, Russia, and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (U.S.S.R.). Ukraine had experienced a brief period of independence in 1918–20, but portions of western Ukraine were ruled by Poland, Romania, and Czechoslovakia in the period between the two World Wars, and Ukraine thereafter became part of the Soviet Union as the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic (S.S.R.). When the Soviet Union began to unravel in 1990–91, the legislature of the Ukrainian S.S.R. declared sovereignty (July 16, 1990) and then outright independence (August 24, 1991), a move that was confirmed by popular approval in a plebiscite (December 1, 1991). With the dissolution of the U.S.S.R. in December 1991, Ukraine gained full independence. The country changed its official name to Ukraine, and it helped to found the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), an association of countries that were formerly republics of the Soviet Union.

Ukraine is bordered by Belarus to the north, Russia to the east, the Sea of Azov and the Black Sea to the south, Moldova and Romania to the southwest, and Hungary, Slovakia, and Poland to the west. In the far southeast, Ukraine is separated from Russia by the Kerch Strait, which connects the Sea of Azov to the Black Sea.

This geogrraphic location makes Ukraine vulnerable for Russian infiltrations and attacks via it's long Northern border with Russian allie Belarus, it's North-Eastern and Eastern borders with Russia, the Sea of Azov, Crimea -which is occupied by the Russian Federation-, the Black Sea, via Transnistria and Kaliningrad in the Kaliningrad Oblast. More than half of Ukraine's border is territory where the Russians could invade. Only the Polish, Slovakian, Hungarian, Romanian and Moldovan borders are rather secure. But these borders can change quickly in years or decades due to world developments, changing regimes and silent Russophilia in countries like Moldova, Hungary, Czech Republic and Slovakia.

Cheers,

Pieter |

|